[raw num=”1″ align=”stretch”]

[bylines]

To those who know her, Michelle Bao’s July 13 tweet was both totally expected and a complete bombshell.

“very excited to announce that i got so burnt out from this year of remote work that today i dropped nearly all of my commitments to visit friends and live out of a minivan for an indefinite amount of time,” she tweeted, attaching a photo of herself sitting next to the small bed in the back of her renovated vehicle.

Bao, a rising junior Computer Science major at Stanford, is one of my best friends from high school. I’ve always known her to be spontaneous and bold — debating those she disagreed with, riding a Ripstik down our school hallways, reaching for the blueberry barbecue sauce at a local burger joint. In 2018, she moved across the country to attend college in California, leaving our North Carolina-based friend group behind. Her 2021 minivan decision was, in this way, a direct spiritual descendent of the past.

But she is also one of the most professionally ambitious people I know. At the start of the pandemic, she juggled a part-time internship at Uber with spring quarter classes. She worked at Bloomberg over the summer of 2020, then, refusing to partake in another year of remote learning, took a gap year to work for the ACLU and the New York Times.

“I fell into this mentality of, ‘Oh, since we’re doing remote work, we can be extra productive,’” Bao said. “But I think I definitely sacrificed personal joy and fulfillment.” When she found herself dissatisfied with her summer research position, she quit, commiting to traveling around the East Coast full-time.

“It’s just something that I’ve been wanting to do for this past year,” she said. “It’s fine that I’m not extracting specific points of value or achieving specific things.”

After rigging up the back of her family’s old Honda Odyssey with a small bed, rugs, curtains and a water pump, she drove from her home in Greensboro, North Carolina, to New York City. There, she spent weeks couch-surfing with friends before making her way up the Northeast. She hunted for free showers and slept in hotel parking lots. She visited thrift stores and ate good food. In Portland, Maine, she ventured alone to a speakeasy and left with two new friends in their mid-twenties.

“I feel like this has actually been the most fun summer I’ve had,” Bao said. “I’m free of commitments, feeling liberated.”

[photo headline=”” description=”” caption=”” credit=”Michelle Bao” src=”<img src=” ” />=”” ALIGN=”full” ]

” />=”” ALIGN=”full” ]

I spent my own summer in a medical school lab at Yale, following a distinct routine: the same oatmeal for breakfast, the same walk downtown, the same benches and equipment. I was funded by a Yale research fellowship that, assuming I worked standard hours, paid less than minimum wage. Part of me could not fathom her life, the uncertainty and fearlessness of it all. But another part of me longed for her freedom — regardless of how much I enjoyed or was learning from my work.

When I connected with friends from Yale also spending their summers in New Haven, Bao’s van life felt even more alien. “What are you doing this summer?” became a popular conversation opener, to which every person, unless they were taking classes, answered with an internship, research role or otherwise career-advancing position.

For many students at schools like Yale and Stanford, summer has become a key period for career advancement. According to the annual summer activities survey conducted by Yale’s Office of Career Services (OCS), in 2020, 25 percent of Yale students held paid internships, while 18 percent held unpaid internships and a little over 10 percent conducted some form of research.

What conceptions of productivity stopped me and my peers from giving ourselves a break and following in Bao’s steps? Was the value gained from our own summer experiences — financial compensation, lines on our resume — worth the sacrifice of freedom? And ultimately, how did my ability to ask these questions reflect my own privilege?

MONEY, OR LACK THEREOF

Like Bao, Will (name changed for fear of employer retribution) traveled this summer. His experience, however, came directly from his employer, the financial services company Citadel, which flew its interns out to a retreat in Palm Beach by private jet this June.

Last year, in a sharp contrast to most other companies, which cancelled their summer 2020 programs or translated them to a virtual format, Citadel rented out five-star resorts in Florida and Wisconsin. For two months, its interns worked in-person in COVID-safe bubbles and were even provided social activities — canoeing, karaoke, golf lessons — for their downtime. This year, though the program returned to offices in New York City and Chicago, the perks remained. In addition to the retreat to Palm Beach, for example, Citadel interns were treated to corporate housing in high-rise buildings, Uber credits for their commutes and covered meals. And, of course, there’s the salary. “I make more in a summer than what my high school English teacher made in a year,” Will said.

But the luxury resorts and apartments come at a high price. Will noted that a typical Citadel intern works twelve hours a day, five days a week — already more grueling than the standard 9-to-5 one might expect of a job or internship. This summer, Will and some of his peers have at times experienced even worse: workdays that extend beyond thirteen hours, with additional tasks to be completed at night from home or on the weekends.

“I wake up, get ready as fast as possible, Uber to the office, stay there from eight to eight, Uber straight back to my apartment, work a bit, go to bed, and then rinse and repeat. The only time I step outside during the workweek is going to and from my Ubers,” Will said.

For Will, the work becomes even more draining when he considers its implications. “At the end of the day, what’s the point?” he asked. “If you’re at a finance firm, then the goal is just to make money for outside investors or the top people at the firm. I would rather work on problems that more directly benefit society, but unfortunately, in the society we live in, there are these perverse incentives to not help other people.”

[pullquote credit=”Will” align=”full” ]I make more in a summer than what my high school English teacher made in a year.[/pullquote]

Lucrative internships in finance or its sibling field, consulting, have an outsized influence over campus culture, noted Diego Haro ’22, a Global Affairs major at Yale who interned at Boston Consulting Group, or BCG, this summer. “The second you get [to Yale], you learn about investment banking and consulting,” he said.

Haro aspires for a future career that will include “impactful, meaningful work” in issues like homelessness, poverty and mass incarceration, he told me. This year, he worked for a public sector client and has a more optimistic outlook than Will about the meaning of his employment. “At the end of the day, if your employees don’t want to do a certain type of work, then obviously, [the company] won’t be doing that sort of work,” Haro said. “I think there are very tangible ways that I’ve learned and seen of actually affecting change.”

BCG doesn’t expect interns to work on weekends and has instituted biweekly mental health check-ins. But the job is still grueling. “I would not say you have a good work-life balance,” Haro told me. “But I would say it’s fair given what you signed up for and what they pay you.”

These considerations loom large for Haro, who was raised in Sacramento in a lower to middle income background. “I’m now almost making more than my parents. It’s kind of crazy,” he said. “That’s part of why I’m working there, the financial stability.”

For Blake Bridge ’23, a Global Affairs major, his State Department internship at the U.S. Embassy in Berlin has had a more direct connection to his future career goals. “[Through studying at Yale] I can learn all I want about international relations. But you can’t learn what it’s like to be a diplomat or to work at an embassy. You have to experience that [in real life],” Bridge said. “I’ve learned a ton, and that’s been vital for me in understanding what I want to do next summer or when I graduate.”

Though his program is remote, Bridge chose to divide his summer between London and Berlin so that he could work the same hours as the rest of his office. Unlike Will and Haro, he has no complaints about his work-life balance and has enjoyed exploring Europe on his weekends.

But Bridge’s experience comes with a caveat: internships in the federal government are typically unpaid. Bridge, who navigated several complications due to Yale’s policies on international travel during the pandemic, supported his work through fellowships awarded by the Jackson Institute for Global Affairs. In this way, Yale students are given a key advantage over students at other universities, who must participate in similar opportunities on their own dime.

[pullquote credit=”Sarah Feng” align=”full” ]I started questioning, was productivity something that was actually making me happy? Or was it the semblance of productivity that was fueling my sense of self-worth?[/pullquote]

Unpaid internships have become flashpoints for discussions over labor exploitation. These conversations date back to 1938, when, following the Great Depression, President Franklin D. Roosevelt passed the Fair Labor Standards Act, or FLSA, which established guidelines protecting workers’ rights and wages. A 1947 Supreme Court ruling set a precedent that labor could be uncompensated if it had training purposes, providing legal justification for unpaid internships. This was reinforced in 2011, when two unpaid interns who worked on the set of the film “Black Swan” sued Fox Searchlight Pictures for violation of the FLSA. The Second Circuit ruled against the interns, arguing that they were not obligated to receive compensation because they were the “primary beneficiaries” of the arrangement, learning more from the company than the company gained from their work.

[photo headline=”” description=”” caption=”” credit=”Sarah Feng” src=”<img src=” ” />=”” ALIGN=”right” ]

” />=”” ALIGN=”right” ]

Sarah Feng ’25 observed that unpaid internships also reflect privilege, as only those with a substantial level of financial security can afford to take them over a paid internship or job. Feng deferred enrollment before her first year — cutting her off from Yale fellowships — to work two unpaid internships: one at the San Francisco district attorney’s office where she corresponded with prisoners and one conducting research for the Virtual Student Federal Service at the State Department. “I was living purely off of my parents’ money and our financial situation,” Feng said. “I was spending eight hours a day doing a lot of work that was giving me a cool experience, but I had other friends who were honestly equally as qualified as me [who] couldn’t take on things like that, and instead had to take on other jobs that were less meaningful.”

Internships often help students explore their interests or provide valuable paths for employment. A 2017 Gallup survey, for example, found that having relevant internship experience more than doubled recent graduates’ chances of having a secure job immediately after leaving school. In this way, the inaccessibility of unpaid internships to some may uphold existing class divides.

Yale and other elite universities have programs to lower these barriers for their students. In 2020, 31 percent of Yale students funded their summer experience with help from the university. Many claim the Summer Experience Award, which provides a stipend for any student on financial aid to pursue an unpaid or underfunded research, arts, government or non-profit position. Students can also access fellowships from a variety of other sources, such as their residential colleges or Dwight Hall.

Jeanine Dames, director of the Office of Career Strategy, noted that this is a huge equalizer for first-generation, low-income, or FGLI, students. “We have not seen a significant difference between our FGLI students and non-FGLI students in the rate they participate in unpaid internships. In fact, we see a slightly higher percentage of FGLI students accepting unpaid internships,” Dames wrote in an email. Dames cited preliminary results from the 2021 OCS summer activities survey, which has not yet been concluded at the time of writing: 72.3 percent of first-generation respondents held a paid or unpaid internship or research position this year, compared to 67.6 percent of non-first-generation respondents.

PRIVILEGE, PRODUCTIVITY AND PATTERNS OF HISTORY

Modern-day internships have their roots in tradesmen apprenticeships dating back to the Middle Ages. The medical field first popularized the term “internship” at the turn of the 20th century, in reference to the period where newly graduated doctors gain more practical training before launching their independent careers. Industrialization drove white-collar industries such as business and engineering to professionalize and adopt their own expectations for experience-based internships. Over the coming decades, Census data indicates that the labor market became increasingly saturated with college graduates, with attendance rates more than tripling between 1940 and 1980. During the same period, companies and universities increasingly expanded their internship programs, cementing internships as an unspoken expectation for many college students’ educations by the end of the century.

[photo headline=”” description=”” caption=”” credit=”Yale Daily News” src=”<img src=” ” />=”” ALIGN=”right” ]

” />=”” ALIGN=”right” ]

The archives of the Yale Daily News reflect this history. Mentions of the word “internship” appeared in medical contexts in the 1920s before exponentially increasing throughout the 60s and 70s. More intriguing, however, are the clear ways in which Yale students have always had exclusive and unique access to internships, both paid and unpaid.

The first non-medical reference to an “internship,” for example, came in 1938. That year, United States Representative Frederick Davenport (NY-R) visited New Haven to interview Yale students for unpaid government internships, which were set aside for “Seniors and Graduates from the leading universities in the country.” In the 1950s, the university sponsored its first official internship program, the Yale Summer Intern Program in Government, which placed students in positions throughout the federal government and provided funds of 50 dollars per week for unfunded opportunities. By the 1960s and 1970s, similar programs proliferated — Urban Studies internships, Dwight Hall internships, public policy internships in Washington coordinated by the now-defunct Summer Term Office — helping students to secure and afford government and nonprofit work. In the same period, fellowships also became available to fund students’ research.

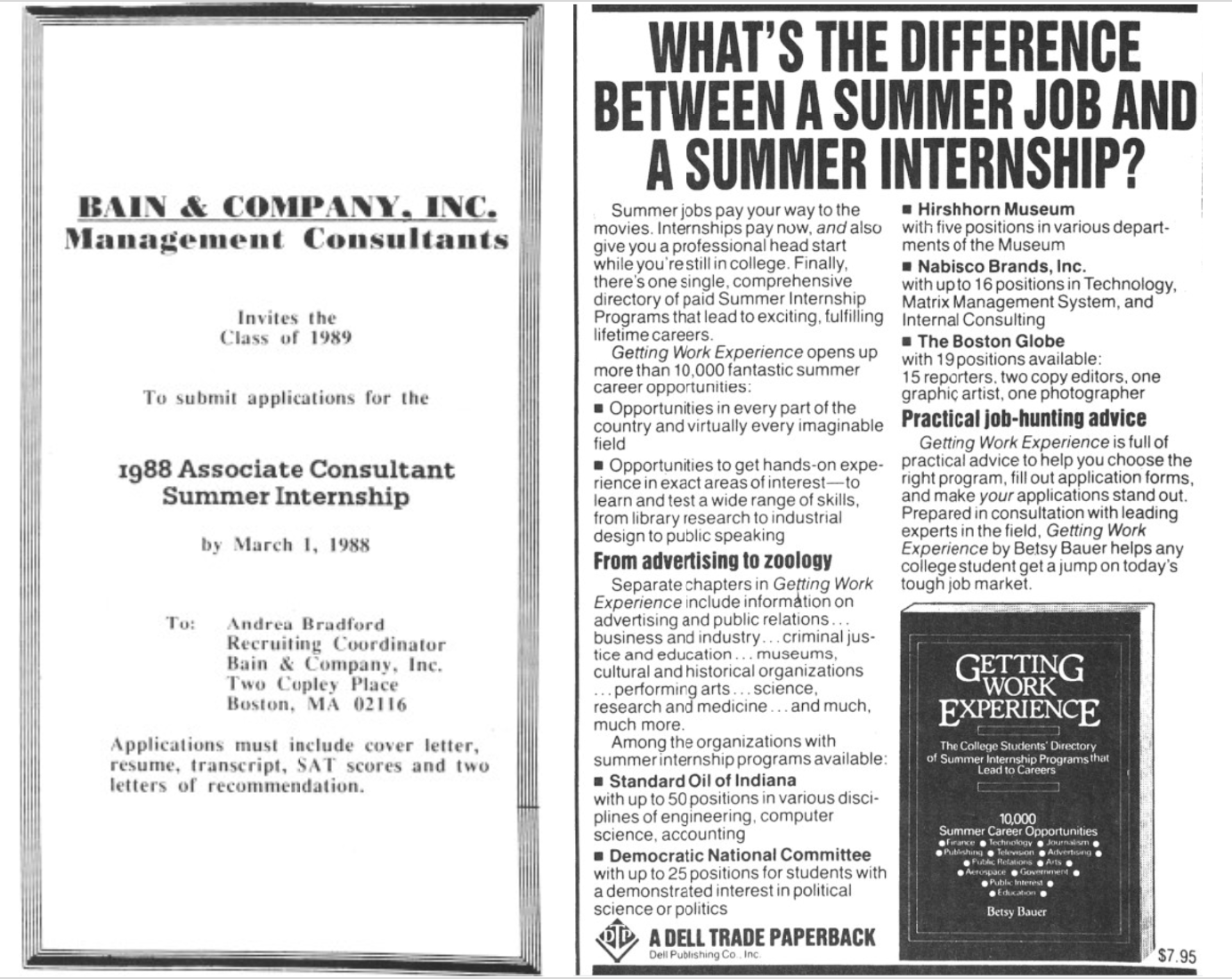

Yale students received special attention from private companies, too. “Who says liberal arts isn’t good preparation for business,” wrote the Connecticut Mutual Life Insurance company in an advertisement in the News for its summer 1968 internship program, which held interviews on campus that February. In 1975, the Summer Term Office facilitated a program to help students find corporate internships, leaning on connections with “alumni in Yale clubs across the country” who specifically “elected chairmen to assist students.” Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, companies such as the New York Times, Goldman Sachs and McKinsey & Company held interviews and information sessions on campus. Other companies, including Procter and Gamble, Grace and Bain and Company, took out ads inviting students to apply to their summer internships.

[photo headline=”” description=”” caption=”” credit=”Yale Daily News” src=”<img src=” ” />=”” ALIGN=”full” ]

” />=”” ALIGN=”full” ]

Yale’s internship culture can, at some points, feel incredibly disconnected from the rest of the labor market. “What’s the difference between a summer job and a summer internship,” read a 1985 ad in the News for a book called “Getting Work Experience.” Yale students, the ad implied, were destined for the latter.

The numbers reflect this: In the Summer of 2020, while almost 67 percent of returning Yale seniors held an internship or conducted research, just 8 percent spent their summers in another type of paid job such as a camp counselor.

The entire concept of internships is, after all, paradoxical for students at schools like Yale. We’re beneficiaries of decades-old institutional privileges that give us the information and financial support to pursue opportunities in white collar sectors like government, academia, tech, finance, and consulting. But beneath all summer internships is a capitalistic system, one that forces us to choose between passion and salary, and one that insinuates that productivity — for-profit or nonprofit, paid or unpaid — must persist, even during summer vacation.

That mentality can be exhausting, Feng observed. “I would sometimes feel unable to move for a while, because I felt I had let myself down the past month, even though I was trying really hard to do what I wanted to do — even though I was already fortunate to have these opportunities,” Feng told me. She, in addition to holding two unpaid internships in her gap year, spent time away from her Bay Area home to live in New York City this summer, working as a creative writing tutor and writing a novel. “I started questioning, was productivity something that was actually making me happy? Or was it the semblance of productivity that was fueling my sense of self-worth?”

Bao, traveling around in her van, unemployed without a clear goal for herself, might seem to be rejecting our capitalistic obsession with productivity altogether. In reality, she was only able to spend a summer unemployed because of multiple layers of financial security. “Ultimately, if my situation was different and I had family members that needed me to take care of them, there’s no way that this would have been a viable path,” Bao said. She emphasized that the various internships she had worked over the past year — internships she accessed in part because “elite institutions give you a huge advantage” — helped her accumulate the necessary savings to pursue her summer travels.

In this way, she is just like any finance, consulting or government intern, deeply intertwined with the privilege and productivity that saturates our capitalistic internship culture. That, she believes, is exactly the point.

“It’s very naïve to think that a personal change can wholly reject a capitalistic mindset,” Bao said. “Rejecting capitalistic values requires you to have embodied them in some other form. And that’s a huge part of capitalism in our current system, a huge problem. There’s no consent. There’s no alternative. There’s nothing else.”

” />=”” ALIGN=”full” ]

” />=”” ALIGN=”full” ] ” />=”” ALIGN=”full” ]

” />=”” ALIGN=”full” ] ” />=”” ALIGN=”full” ]

” />=”” ALIGN=”full” ]