UP CLOSE:

With success against the spread, Yale men’s basketball wins support of sports bettors

Sports betting has created an unusual source of national attention for the Bulldogs this season, as angry strangers comment critically on players’ social media accounts and the Yale program as a whole still feels underestimated.

Dave Portnoy, brazen internet celebrity, pizza critic and founder of Barstool Sports, placed his bet at 3:59 p.m. on Saturday, Nov. 23, 2019.

At the time, most in New Haven concentrated on the Yale football team, which trailed Harvard by 14 in the fourth quarter at the Yale Bowl. But Portnoy made his pick on Yale men’s basketball, selecting the Elis to defeat Big Ten opponent Penn State. The wager? $10,000, submitted a minute before tipoff at 4 p.m. as the teams finalized preparations for their Saturday afternoon showdown in State College, Pennsylvania.

And for the next two hours, Portnoy likely sat on the edge of his seat, gaining faith in his decision as the game progressed. The Bulldogs led 31–21 at halftime, while football fans stormed the field after Yale’s double-overtime comeback at The Game in distant New Haven. The Elis’ advantage held strong into the second, expanding to as much as 16 in the half as guard Azar Swain ’21 poured in a game-high 24 points. With 3:32 to play and a 56–46 Yale lead, Portnoy’s payoff of $82,500 seemed imminent, until a 12–0 run from the Nittany Lions allowed them to escape with a 58–56 win in the closing minutes. Portnoy did not respond to a request for comment.

An angry video and a screenshot of the late-game play-by-play publicized his failed bet to 1.1 million followers. “@YaleMBasketball killed me,” Portnoy’s Twitter bio read for the next month. Captain and guard Eric Monroe ’20 heard about the burst of online activity when he checked his phone afterwards.

“For a guy who probably doesn’t know much about college basketball, I don’t know why he’s placing $10,000 on a game,” Monroe said. “It was kind of a weird thing to take in after a game because we were obviously so disappointed. We had that game more than secured as a win… [it was] funny but very depressing, because that would’ve been a very important win for us. [The betting] is funny and amusing to me, but it’s also a lot of people who just use it as a way to get angry.”

The wager, in many ways, only marked the beginning of sports bettors’ obsession with Yale basketball this season. Two-and-a-half weeks later, the Bulldogs ranked as the most “profitable” team of the 353 programs in NCAA Division I men’s basketball — Yale had covered the spread, the sports books’ projected outcome for the result, in nine of their 10 games. Although oddsmakers have adjusted their spreads during Ivy League play, Yale remains in the top decile of “profitable” college basketball squads. Their 17–9 record “against the spread” nearly matches its 20–6 overall mark in DI contests. The betting has given the Elis an unusual source of national attention as they seek another Ancient Eight title.

Regulations around sports betting and its legality have shifted rapidly in recent years, and Yale players accustomed to an average of 1,500 home supporters each game are caught in the middle of the betting flux. Gaming publications preview money lines and predictions about the team online, angry strangers comment critically on players’ social media accounts, and the Eli program as a whole — the often profit-generating product for an increasingly national betting audience — still feels underestimated.

A CHANGING LANDSCAPE

Across the country, the approach of the NCAA Tournament coincides with an influx of sports betting. According to a 2019 report from the American Gaming Association (AGA), fans were expected to wager around $8.5 billion dollars on March Madness last year. 47 million Americans intended to bet on the event, with an increasing portion, 4.1 million, anticipating the use of regulated, legal apps or casino sportsbooks. According to AGA President Bill Miller, fans expected to bet 40 percent more on the 2019 NCAA Tournament than they did on the Super Bowl that year, and for the first time in decades, many could do it legally.

A May 2018 Supreme Court decision in Murphy v. National Collegiate Athletic Association struck down the Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act of 1992 (PASPA) on the basis of the 10th Amendment. Mark Hichar ’81, a Boston-based shareholder of the Greenberg Traurig law firm and an adjunct professor in gaming law at the University of New Hampshire’s Franklin Pierce School of Law, said concerns about game fixing and point-shaving scandals inspired PASPA. The law essentially outlawed sports betting nationwide except for in Nevada, but Hichar said an illegal sports betting market with annual betting handles between $50 and $300 billion persisted.

PASPA was also known as the Bradley Act, named after former Princeton basketball star and then-U.S. Sen. Bill Bradley.

“[PASPA] put the onus on the states, it commanded them not to pass these laws, and it was on that basis that it was struck down by the Supreme Court,” Hichar said. “[After the ruling, Delaware was] the first state to allow sports betting within their boundaries. New Jersey followed soon after. As we speak, somewhere around 20 states, including the District of Columbia, have authorized sports betting.”

Hichar said that of those 20, about seven have yet to put their laws into effect, since they have yet to pass the regulations necessary for implementation.

Tribal conflicts with Mohegan Sun and Foxwoods have complicated the legalization process in Connecticut, where sports betting remains illegal, Hichar added. Rhode Island, where Yale defeated Brown in January, is one state that has legalized mobile sports betting. Brothers Dave and Cam Rosa cheered on Yale from the first row at Brown’s Pizzitola Sports Center.

The two Providence locals said being able to bet on the contest was “the final straw” that brought them to buy tickets and watch. Unfamiliar with any names on the Yale roster, they supported players by their numbers instead. With the win, Yale improved its record against the spread to 13–3.

“Numbers don’t lie,” Dave Rosa said. “You gotta score points. Johnson and Wales, [Yale] beat them by 50. You can play basketball one way or another if you beat a team by 50.”

Except for Massachusetts and Connecticut, some form of sports betting is legal in all states where Yale plays Ivy League games. Massachusetts is currently considering legislation that would make sports betting lawful.

Hichar said a large illegal market for sports betting still exists, making data on betting handles hard to estimate and verify, but legalization has also helped detect small instances of tampering and betting irregularity (in tennis matches, for example) through digital oversight of wagers. For the Elis, that’s not a concern.

“I don’t really care about what anybody else is doing,” forward Jordan Bruner ’20 said. “That doesn’t affect me at all honestly. If people are making assumptions that we’re going to lose a lot because we play a high-major team, then they probably don’t see us play very often because we got a lot of high-major athletes and a lot of high-major talents… We know what we have in the locker room and we know we’re going to come out and compete and just play as hard as we can. Wherever the chips fall is where they fall.”

A decade or two ago, when the only legal point-spread betting took place in Nevada, accessible, updated information about Ivy League basketball teams was hard to find. When betting against the spread, one bets that a team will not just win or lose, but will do so by a certain margin that oddsmakers at sports books set prior to the game, increasingly through the use of algorithms.

A New York Times story from 2009 documented the habits of professional bettors who occasionally bet on the Ivy League in Las Vegas. One of them, Alan Boston, subscribed to Ivy League student newspapers for the latest updates on each team and its roster. Because the papers do not publish on Saturdays, he told the Times that he avoided betting on the Ancient Eight’s Saturday games, the second legs of back-to-back weekends often filled with unpredictability. Wagering on lower-profile Ivy League teams could offer sports bettors with the right information a unique advantage.

“When there is imperfect information, people exploit that,” Hichar said. “People don’t tend to know the teams in the Ivy League as well as they know those in the SEC, with the result that the spreads for the Ivy League game, probably, are of lesser quality than the spread for other games where they have known teams. I think that that tends to attract bettors who believe they have better knowledge than the people who are setting the spread. So if you think the spread is ridiculous because Yale is not going to lose to North Carolina by 20 points… [that] attracts money to games where there’s a perception that there’s imperfect knowledge.”

“We know what we have in the locker room and we know we’re going to come out and compete and just play as hard as we can. Wherever the chips fall is where they fall.”

—Forward Jordan Bruner ’20

Yale lost to the Tar Heels by three in December, 70–67, covering a spread that the sports booksset at 6.5. Today, while larger programs continue to receive more coverage than the Elis, access to online statistics has decreased the information gap. Still, Yale plays on national television far less than the average Power Five conference team, and sports books do not accept bets for the game or two Yale plays against DIII competition each year. This season, sports books did not set money lines for Yale’s games with Oberlin and Johnson and Wales.

Hichar, who lived in Ezra Stiles when he was a student, often walked across the street to Payne Whitney for games. He and his friends played a lot of bridge, he said, but betting was nowhere on their minds. Easy access to mobile betting — legal and illegal — has changed that for some Yale students today. The NCAA prohibits all of its student-athletes from engaging in sports betting at any level, and while sports betting remains unlawful in Connecticut, illegal online betting is extremely common.

Andrew, a Yale sophomore who does not play a varsity sport and preferred not to share his last name with the News, has bet on the Bulldogs twice this season. He lost $10 when Harvard beat Yale by a point in February and won $15 when the Elis dominated Princeton on the road a week later.

“Especially if it’s not high stakes, I feel like for me it’s definitely just the adrenaline rush of it,” he said. “Being able to say like, ‘Oh my god, I have a little bit of a stake in this game,’ it’ll make it more enjoyable for me to watch, and I think it allows me to understand the mechanics of the game a lot better as well just because I’m paying more attention.”

BETTING ON THE BULLDOGS

Head coach James Jones thinks success against the spread speaks to a perception battle the Bulldogs perpetually face. The casual fan rarely associates Yale, which has ranked top 50 in the nation for much of this season, with a strong basketball program.

“The part that hits me is that we’re always being doubted,” Jones said. “One of my former statistical guys sent me something about us being like the number one team in the country over the last 10 years with beating the spread. So for 10 years we’ve been disrespected a little bit in terms of how people perceive us… It’s just that the perception of Yale basketball hasn’t got to the point where it should be. That’s the way I look at it. They underestimate us.”

Yale’s winning percentage against the spread in the 2010s was 58, the highest in the country.

“For 10 years we’ve been disrespected a little bit in terms of how people perceive us … [T]he perception of Yale basketball hasn’t got to the point where it should be. That’s the way I look at it. They underestimate us.”

—Head coach James Jones

Jones pointed to trends in Ivy League preseason polling to illustrate his point as well. In 10 of the past 14 seasons, Yale has outpaced projections in the Ivy League Preseason Media Poll. Picked to finish third at the start of this season, the Elis will improve that statistic at the end of the weekend. Yale is guaranteed to finish either first or second in the conference no matter the outcome of its final regular-season contests at Dartmouth and Harvard. At the same time, Jones said he would not want it to be the other way — better Yale beat the spread than be the worst team against it, failing to fulfill expectations every time.

Players have encountered the same chasm between perception and reality. Once, guard Mike Feinberg ’22 started chatting with two kids in New Haven about basketball.

“I told them I played at Yale, and they didn’t understand,” Feinberg said. “They didn’t even know we had a team. One was a freshman in high school, which is pretty old to not know that, and the other was his younger brother in seventh grade… It’s kind of crazy how the average basketball fan doesn’t know that Yale basketball is a prominent Division I basketball team and that we’re good, that we can hold our own against the best teams.”

Feinberg said he thinks it’s “wild” how adults bet thousands of dollars on the performance of college athletes. He said the betting makes him a little uncomfortable, but he understands its place in sports, an extra draw for the average fan.

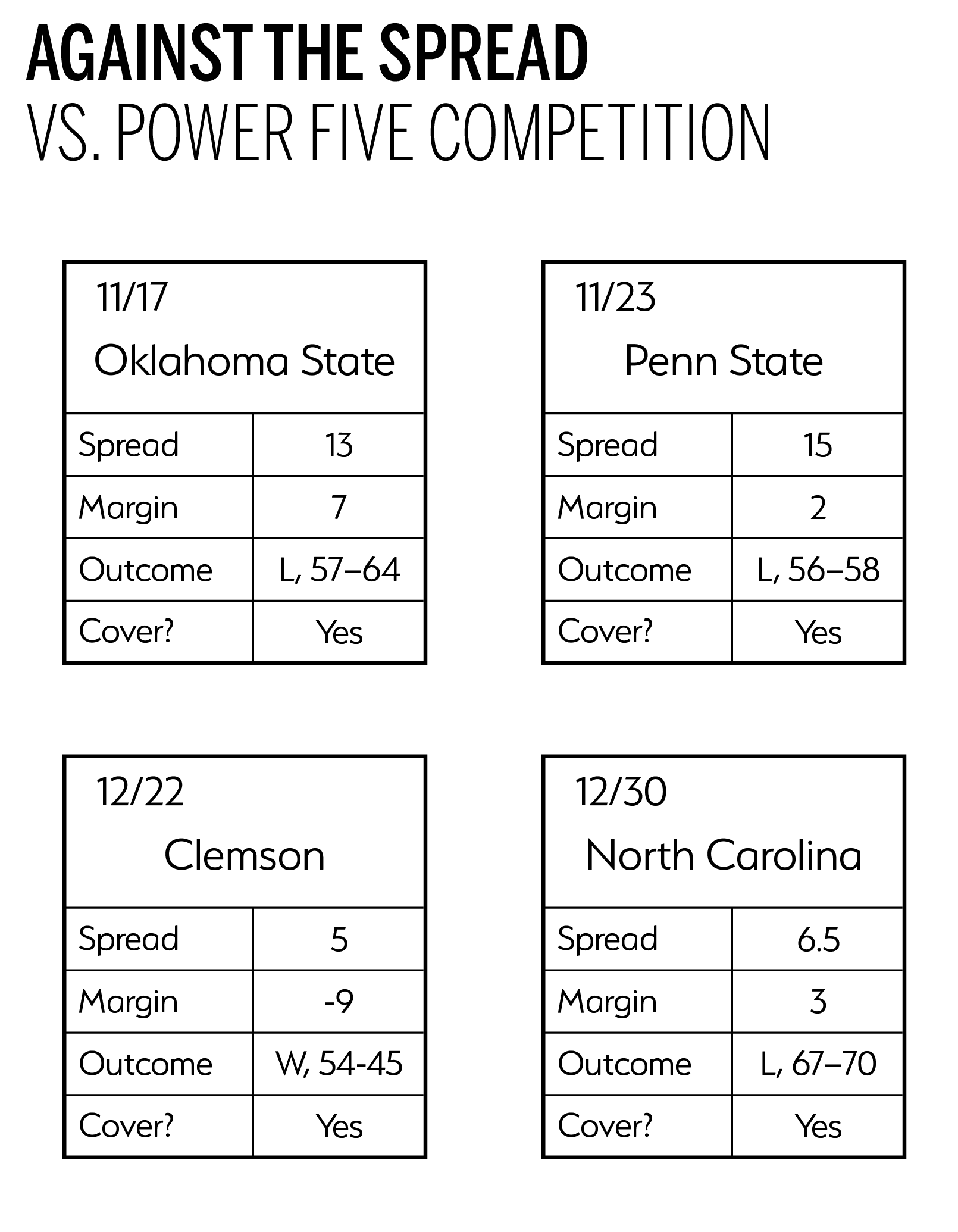

The Bulldogs have beaten the spread in every contest they have played with a Power Five opponent this year. In Stillwater, Oklahoma, Yale fell by seven, beating a spread that projected they would lose by 13. At Penn State, to Portnoy’s distress, the Elis lost by two, but anyone who picked them to cover the spread, set at 15 points, made a profit. A few days before Christmas, the Bulldogs’ nine-point win at Clemson saw them beat the spread again. And in its next game, Yale lost to North Carolina by three, improving its record against the spread to 11–2.

Frank Krugel, an usher who works every men’s basketball game at John J. Lee Amphitheater, said some of his friends started betting on Yale after its narrow loss in Chapel Hill two days before New Year’s. Sports fans first, his friends come to watch games live.

“They kind of realized what a good team Yale is,” Krugel said. “North Carolina is kind of having a bad year, but still, to be in the same ballpark as them says a lot of things.”

Many in the sports betting world already had their attention piqued. Shane Messer, who runs a Twitter-based business on the account Puckline Papi in which customers pay him for sports betting recommendations, said he began betting on the Elis after their performance at the November Penn State game.

By now, he said Yale has essentially become an “auto-bet” for him, a team he automatically chooses to bet on each game they play. Messer estimates he has sold recommendations to bet on Yale to at least 600 people since Portnoy’s big wager on the Penn State game.

“I like to think I got on the Yale-against-the-spread trend pretty early this season,” Messer said. “Seven times out of 10, they’re winning [me money]… You know how it works with Barstool and Dave Portnoy. When they tweet about something, it’s got a million views and interactions. That alone could help Yale basketball betting on its own.”

The Bulldogs followed their performance against Penn State with five straight wins against the spread, driving up to Massachusetts as the most “profitable” team in the nation by mid-December. An 83–80 overtime win helped the Elis improve their actual record, but UMass guard Carl Pierre hit a three-pointer in the final seconds to shrink Yale’s ultimate advantage to three. Monroe and forward Paul Atkinson ’21 both defended Pierre on the play, contesting the shot without risking a foul. With a six-point lead, Monroe said he simply wanted to avoid giving Pierre a chance to convert a four-point play.

The conversion helped the Minutemen cover the spread, and what felt like a meaningless, late-game three-pointer to Yale players (that was irrelevant to the outcome of the game) incurred the wrath of bettors on Twitter. “Paul Atkinson is a hoe for not stepping up to contest but why tf was Eric Monroe backing up the entire time?” one user commented on Twitter. “Not only was he back pedaling [sic] the entire way but he kept looking back for the screen and fell for it.”

“These Twitter accounts that follow who beats the spread consistently like Barstool accounts and stuff, we’re popping up on tweets [that say] Yale’s very good against the spread, like ‘Bet on them, bet on them,’” Monroe said. “So people do it and people get mad when we don’t, which isn’t very often I guess… [After UMass] some guy just went on a rant on Twitter, like what the hell is Monroe thinking and Atkinson’s head is not even in the game. It’s like, dude, do you even understand basketball? We’re just trying to win the game.”

Even after failing to cover the spread at UMass, by winter break, the Yale basketball betting craze had spread from coast to coast.

Back at home in California, Colman Seery ’22 was buying jeans at a Levi’s in the mall when a retail worker there revealed his Yale basketball betting habit.

“Somehow one time, he saw me on my phone on Yale, and he’s like, ‘Oh, I bet on Yale basketball,’” Seery, who has never watched a Yale basketball game, said.

But despite beating the spread in its Ivy-opening games at Brown, the Bulldogs’ success against the spread has taken a dip in 2020 and during conference play. Yale went 11–2 against the spread this fall, but has regressed to 6–7 in the new decade. Oddsmakers have corrected spread lines, making it more difficult to beat teams by significant margins.

Sports books projected the Elis to win by 20 at Howard, ranked one of the worst teams in DI basketball, but Yale could only manage a 14-point victory. A similar scenario played out when the Elis hosted Cornell, defeating the Big Red by 15 but unable to cover a 17-point spread. Yale has failed to cover in other February games against Harvard, Penn at The Palestra, Cornell in Ithaca, and Penn and Princeton at home. Feinberg said Swain, who scored a career-high 33 points in the Harvard loss but missed a free throw that would have sent the game into overtime, received hateful comments afterwards from some who had bet on the nationally televised game on his Instagram.

Messer said that games with national audiences typically draw greater betting activity, adding that a gradual adjustment of the spread is a common occurrence in sports betting. As more people put money on the Bulldogs, winning a profit becomes more difficult.

“[Betting on Yale] is definitely something that I would say a lot of bettors are missing out on, but I can guarantee you the guys making the lines are not missing out on that,” Messer said. “They’re definitely aware of how dominant Yale has been against the spread this year… It’s big money that moves the betting line. If somebody comes in and hammers the Yale spread for $250,000, they’re going to move the betting line the other way just to entice some people to bet on the other side.”

Still, online sports betting publications have covered Ivy League games all season long. Google Yale and its opponent for any given weekend, and betting guides appear. A search of the Yale-Princeton game in mid-February — a nationally televised contest that attracted an especially high volume given that the NBA was in the midst of its All-Star weekend — yields stories from The Action Network, FanDuel, Sports Chat Place, Winners and Whiners and CBSSports.com. Most previews offer broad storylines, review each team’s success against the spread and promise betting advice on the game. Some, like stories in OnlineGambling.com, occasionally draw quotes from the News.

“A GOOD THAT PEOPLE CONSUME”

The Supreme Court’s 2018 decision in Murphy v. NCAA and the subsequent legalization of sports betting in several states have raised questions about where players, both professional athletes and student-athletes, fit into the recent changes.

According to USA Today, NCAA leadership announced in 2018 that the association remains against sports betting and would not plan on seeking an “integrity fee” from sports books — money that would help offset expenses associated with monitoring for potential betting irregularities. Their announcement came about a month after the Supreme Court decision, while the NBA’s decision to pursue integrity fees came in May 2018. Mike Bass, an NBA spokesman, also cited expenses in an interview that month with the Associated Press, additionally making the argument that the NBA is an “intellectual property creator” of basketball games that enable sports betting to occur.

A month before the decision, a joint statement from player’s unions for the MLB, NHL, NFL and NBA also declared their desire for athletes “to have a seat at the table to ensure that players’ rights and the integrity of our games are protected.”

“The leagues take the view that, without their products, sports events, sports betting wouldn’t exist,” Hichar said. “Thus, their view is that they should be entitled to some compensation to the extent that sports betting occurs with respect to their products.”

However, Hichar said he does not see a scenario in which collegiate student-athletes earn direct revenue from sports betting. Plus, in some states, although sports betting has become legal, betting on NCAA competitions is still not. For example, the proposed legislation in Massachusetts, Hichar said, would not permit any betting on NCAA competitions regardless of where they take place.

For some at Yale, a school rarely included in the debate around college athlete compensation, the argument resonates. Feinberg said he personally believes players should receive a portion of all revenue related to collegiate sports made by anyone.

“I’m a big believer that [if] people produce something that people care about, it’s a good that people consume,” Feinberg said. “People consume our basketball games. They watch our games, they get enjoyment out of it and all that. And it comes at a price and people pay that price… What would the games be without the players? It wouldn’t be a basketball game, you know? What would you watch? The refs and the coaches?”

Monroe said he has long been in favor of college athletes getting the opportunity to make money off their likenesses. Last fall, the NCAA announced a vague step to allow college athletes to “benefit from the use of their name, image, and likeness.” The NCAA Board of Governors issued the announcement a month after California passed legislation that would make it illegal for colleges to prohibit their student-athletes from earning income on endorsements, social media advertising or other related activities. Others do not think the ongoing legalization of sports betting complicates the conversation. As Jones pointed out, sports bettors can always lose — and indeed, have lost — money when they wager on the Elis.

Regardless, as March Madness nears, wagers are set to increase in both size and quantity. The Bulldogs, who clinched an Ivy Madness berth with a win over Penn last Friday, hope two wins at the Ancient Eight tournament can facilitate a second consecutive NCAA Tournament appearance.

Some fans might be surprised by an upset, but the sports bettors who have followed the Elis from afar almost all season long would not be.

“They’ve exceeded the oddsmakers in every one of those [Power Five] games,” Messer, the Puckline Papi owner, said. “If I was a team in March Madness and I ended up drawing Yale, I’d be a little bit concerned.”