After life: Muslim deathcare in New Haven

Secular regulations hinder Muslim burial practices in Connecticut

When a Muslim woman dies in New Haven or a nearby town, Sana Fatima Farooqi is informed by the local imam. She finds someone to take care of her sons for the hours that she will be gone. Then she messages one of her WhatsApp groups — “Gosl Sisters Group” or “Washing and Shrouding CT” — to find two to five women who will join her to wash the body of the deceased woman in the Muslim ritual of ghusl before the woman is shrouded and laid to rest.

When she arrives at the funeral home, Farooqi prepares warm water scented with camphor oil to wash the body. Sometimes the home will have running water available in the preparation room. If not, she and the women helping her carry buckets of water for the washing. Out of respect for the modesty of the deceased woman, Farooqi covers her from neck to foot in a white cloth. Just as Muslim women cover themselves in life, they give the same respect to a Muslim sister in death.

The hardest part for Farooqi is washing the breasts and genitals without ever looking at them. The women always wash the right side of the body first, then the left. They repeat this process twice, more if necessary. They must not clip her nails. They must not cut her hair. The body is sacred, as is her resting soul.

Sometimes they must clean blood that trickles from the nose or from exposed wounds on the body. Farooqi takes care not to let any blood get on the white sheet that will shroud the woman in the grave. The cloth, called the kafan, must remain pristine.

Once the washing is completed, Farooqi will dry the body and perfume it with camphor, sidr (jujube) leaves or scented oil so the woman smells as if she had just taken a bath. They dab the scented oil on the parts of the body that touch the ground when Muslims prostrate themselves before God. The forehead, the tip of the nose, the hands, the knees, the feet — these are the places where you are closest to God.

Finally, the women take three seamless white cotton sheets and wrap the body, folding the right side of the cloth over the left. When Muslims bury the body the traditional way, in a shroud without a burial container, the fabric decomposes and the shroud, along with the body, returns to the earth.

~~~

I met Farooqi at the mosque on George Street. She invited me to sit with her on the carpet. The material was scarlet and gold-patterned, vibrant against the black velvet skirt beneath her knees.

From the outside, a passerby would never guess that the unassuming two-story New England-style house with the white cladding, pitched roof and dormer windows is a mosque. But for the Muslim community in New Haven, finding a way to practice their faith within a secular context is not something new but a fact that they have long accepted. The daily call to prayer sounded quietly within the walls of the mosque; in this country, public broadcasts of the adhan are inconceivable. I would soon learn that in death practices, too, Muslims in America have had to learn to adapt.

Erum Hassan

Small-boned and bespectacled, Farooqi’s soft-spoken voice belies the hefty responsibility she bears in the local Muslim community. Farooqi manages a loose coalition of about 10 women who volunteer their time and, in some cases, money, to carry out ghusl for any Muslim women who pass away in New Haven.

“A lot of people are scared to do it because they think, ‘It’s a dead body,’” said Farooqi. “But I think, what if it were me? Who is going to do it for me? Everyone passes away, so you feel honored that you can help somebody in that state.”

For Muslims, washing the body prior to shrouding and burial is obligatory, according to hadith, which are the recorded words and actions of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It is written in hadith that when the daughter of the Prophet Muhammad died, he gave instructions to women to wash her three times or more, with water and sidr and camphor. Muslims today continue to follow these instructions on how to wash the bodies of the deceased.

Farooqi rarely knows the families of the women whose bodies she washes. She has met families from Bosnia and Bangladesh, families who don’t speak English and families who have lived in Connecticut all their lives. Since 2012, she has washed the bodies of over 20 women.

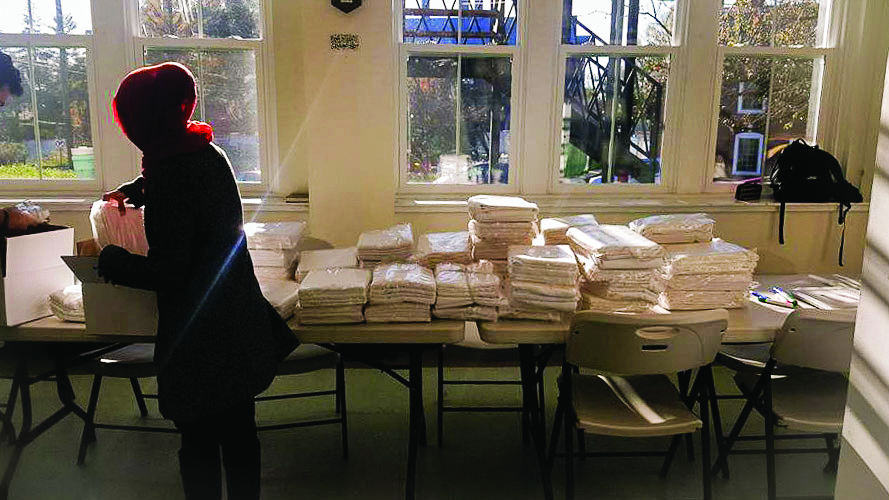

The women who assist Farooqi are usually younger, since the washing involves lifting the body, requiring physical strength. Most are devout and pray five times a day. For many, their motivation is deeply religious. Farooqi and the women who volunteer their time to do ghusl never charge for what they do. Sometimes, appreciative family members will give them some money to replenish ghusl supplies. Every few months, Farooqi purchases towels, soap, camphor, cotton buds, Q-tips and other materials for ghusl, usually with her own money. Recently, Farooqi has begun using burial kits provided free of charge by a nonprofit organization called Akhiri Tohfa based in Connecticut.

“She is not alone in what she does. In Windsor and Bridgeport, Orange and Weston, other Muslim sisters like Farooqi take the lead and organize similar teams to wash the bodies of women in their communities who pass away.”

The women on these ghusl teams have a spiritual connection to these rituals and feel an obligation to perform ghusl. Based on Islamic teachings, if someone in the community fails to carry out this responsibility, there is a sin on the whole community.

The ghusl ritual is a cornerstone of Muslim deathcare practices. “The washing of the body is integral,” said Omer Bajwa, director of Muslim life for the Chaplain’s Office at Yale, “Islam doesn’t have many requirements [for death rites] but the washing of the body is one really prominent requirement.”

According to Bajwa, Islam sees death as a departure from our mortal life where the body is fundamentally vulnerable to degeneration. “Islam is very realistic about the human body and human limitations,” he said.

In line with this thinking, the ideal Islamic burial is simple. Muslims prefer not to use a casket for burial and certainly not a burial vault, a concrete container that encases the casket and prevents the grave from sinking. In strict Islamic tradition, Muslims are laid to rest in a simple burial shroud in the soil.

Bajwa quotes a verse from the Quran to me: “From the earth We created you, and into it We will return you, and from it We will extract you another time.”

For this reason, embalming is also frowned upon in the religion. By wrapping the body in nothing but three plain cotton sheets, the body can naturally decompose and return to the earth.

Erum Hassan

But in practice, very few Muslims are able to fulfill their vision of a simple Islamic burial. Many modern cemeteries have regulations that require burial vaults. One such cemetery is Beaverdale Memorial Park, a modern nonsectarian cemetery in New Haven founded in 1929.

The manager, Dan Krueger, has a neat, white beard that trims his slim face. He has been working at the cemetery since he was 35 years old. He is soft-spoken and kind, almost as if he is anticipating what you are about to say. He says “yes” a lot.

At Beaverdale, it is a requirement that all caskets are encased in a burial vault. The reason is practical: Without the concrete vault to prevent the grave from sinking, the ground covering the burial site can drop several inches. It would be harder to maneuver trucks and equipment and excavators over the grounds. Visitors could trip.

When Muslim or Orthodox Jewish families approach Krueger to help with the burial of their loved ones, Krueger has to explain that regulations require the burial vault for safety reasons. State regulations on burial tend to be permissive, according to Krueger — the body doesn’t have to be embalmed by state law and burial vaults are not required.

However, cemeteries tend to set stricter policies. “We put in regulations so we can maintain the cemetery in the manner we think is fitting,” said Krueger. Being the final resting place of loved ones, a cemetery has to project an atmosphere of serenity and order befitting of the dead. Sunken graves, overgrown grass, and faded plastic flowers littering the grave sites are high on the list of things that Krueger tries to avoid.

Since he was the imam for Masjid Al-Islam from 1996 to 2001, Saifudeen Hasan has been responsible for managing funerals for the mosque and its members. He has noticed that in the past 10 years, cemeteries have started imposing more restrictions on burial procedures.

There is a cemetery in Enfield, Connecticut, where Muslims in New Haven have been buried for over 25 years. After years of burying Muslims the traditional way, without a casket or vault, the cemetery began imposing requirements on using a burial container. Hasan explained that the cemetery was concerned because of its proximity to residential housing and the risk that human remains could contaminate the water.

There’s nothing in the Quran that says the use of a burial container is strictly forbidden, but Muslim burials without a vault or casket are a matter of tradition.

“Sometimes, you have to conform to the state laws as long as it’s not completely against Islam,” said Hasan. “If it was, we would try to go to the state to make exceptions for religious reasons.”

However, given the high cost of funerals, the requirement on burial vaults only increases the financial hardship of a loved one dying.

Death is expensive in America. In 2017, the Bureau of Labor Statistics found that the price of funerals in the United States had risen almost twice as fast as consumer prices for all items since 1986. There are transportation fees to pay the funeral home, burial plots which can cost upward of $1,000 and burial caskets priced at $2,000 or more, among other costs.

Muslims funerals are considered to be on the cheaper end of deathcare rites: Hasan estimates the average Muslim funeral would set a family back by about $5,000. In comparison, the average cost of a funeral with a burial and vault in 2017 was $8,755, according to National Funeral Directors Association statistics. Still, for many members of the mosque, he says, cost is an issue.

“Our community is more blue-collar taxi drivers and social workers, whereas a lot of other communities have doctors and lawyers and engineers,” Hasan said. According to 2017 data by the Pew Research Center, Muslim Americans report lower household incomes and are less likely to be middle class than the general population.

“Muslim families, especially Muslim American families, don’t always have the money to pay for it because they don’t have the insurance,” said Hasan. “So a lot of the time the cemetery will waive the fees or the masjid pays for the funeral.”

But the mosque does not always have the funds on hand to cover the funeral and burial costs of their members. When accounts are running low, the mosque leaders will appeal to the congregation for donations to contribute to the funeral expenses of deceased members. If members don’t have the money, the mosque makes an appeal to other mosques in the area.

Between the Muslim communities in Orange, Hamden and New Haven, they have always managed to pull together the funds in the end, Hasan said. He cited the Muslim concept of “Sadaqah,” or voluntary charity, as the reason for the mosque to shoulder the financial burden for families that cannot afford it.

“Honestly, economically, people are struggling right now so the donations are not as great as they used to be in the past,” said Hasan.

Technically, the Connecticut Department of Social Services offers burial assistance of up to $1,400 for individuals with very limited means. But in practice, Hasan says the assistance has not been immediately useful as it takes days to process.

Since Muslims do not embalm the body, they prefer to bury the dead as quickly as possible, within 24 hours. If they delay until after state assistance is approved, the body will deteriorate.

Hasan recently buried a Muslim man whose family could not afford the funeral. Although they applied for state assistance, it took too long and by that time, the mosque had already covered funeral expenses.

“We don’t get any support from the government,” said Hasan. “Everything is done individually by the mosque.”

~~~

When Farooqi’s father passed away seven years ago, she inadvertently found herself becoming acquainted with the rituals and regulations of death — both Islamic and state-imposed.

Connecticut law generally prohibits people from bringing dead bodies into their homes, unless they have special permission. But for Farooqi, part of Muslim tradition is that a body should never be left unattended.

Farooqi gained permission from the state to bring her father back home where she stood vigil over him through the night, saying prayers over his body. Outside, a state official was parked all night to ensure that the body was buried the following morning in line with state health and safety regulations.

At that time, the only Muslim cemetery in Connecticut was located in Enfield, almost 60 miles and an hour’s drive from New Haven. So to Enfield Farooqi went.

For a Muslim, it is ideal to be buried in a Muslim cemetery. Bajwa explained that the idea of community is deeply rooted in Islam. Even after death Muslims see themselves — irrespective of race, nationality and ethnicity — as part of a global ummah, or global Muslim community.

“These are people who you will be resurrected with on the day of judgement,” Bajwa explained, “Muslims believe at the end of time, it was prophesied by the prophet that all souls will be resurrected from the graves. These are brothers and sisters of faith, co-religionists, that you will be resurrected with before you go to meet god.”

For many years, Enfield was the only option in Connecticut for Muslims who wanted to stay together as a community after death. That changed three years ago, when the Tariq Farid Foundation, a philanthropic organization that has funded U.S. soup kitchens and the rebuilding of schools in northern Syria, opened a second Muslim cemetery in Cheshire, just a half-hour drive from New Haven.

There is still no Muslim cemetery in New Haven, however. For the Elm City’s growing Muslim community, it may be quite some time before that becomes a reality.

~~~

After her father passed away in 2012, Farooqi felt an urge to give back to her community and attended a workshop by Sister Matiniah Yahya to train women in washing and preparing bodies.

Farooqi didn’t know it then, but Yahya would become instrumental in mentoring Farooqi in the ghusl process. Eventually, Yahya passed the role of leading the women who do ghusl in New Haven to Farooqi.

Yahya has been involved in the ritual washing of bodies for most of her adult life. She was 21 when she first participated in a ghusl for a dead person. The imam at a mosque in Quincy, Massachusetts, had called to ask if she could help wash bodies — they were short one person. Her heart pounded as she entered the preparation room where she was to assist the ghusl team in the washing. She told herself, “Don’t faint, just stay there.” She said a prayer to calm herself.

The room was very hot. The air was thick with the piquant aroma of camphor and sweet aroma of oils for ghusl. But despite the heat and her nerves, she felt a sense of calm. The women were all quiet as they methodically worked. All attention was on the body.

“Everything became real to me at that point, all the questions about who is going to wash me? Am I going to be too fat for them to roll over? What is it going to be like? My family, are they going to be here? And the angels are going to come and question me?” said Yahya.

When she arrived in Connecticut after getting married, women were doing ghusl without formalized classes on the ritual. Motivated by her knowledge of Islamic theology, Yahya developed a detailed three-day workshop that explained the scriptural basis for ghusl, examined the ritual’s origins in the teachings of the Prophet Muhammad and taught participants how to wash and shroud dead bodies.

Back then, a large group of stay-at-home wives and mothers volunteered their time to do ghusl. But it has since become harder to find women to help. In the past 15 years, Yahya has noticed more women going back to school or work, with less and less time to volunteer.

Yahya and Farooqi have begun to reach out to towns around New Haven to find other women willing to shoulder the responsibility of ghusl. They have a list of women they know they can call when a Muslim sister dies. But Yahya admits it takes a special kind of person to do this task.

~~~

On the day I met Farooqi in the mosque on George Street, a crying toddler being consoled by his older sister — barely adolescent age herself — and an elderly woman in a hijab sat in the corner of the room. When Farooqi, the girl and the elderly woman lined up for the sunset prayer, they stood from youngest to oldest, a physical reminder of the inevitability of aging and mortality.

“I have seen so many people who have been dead that I [often] think about my own death and what am I going to leave behind,” said Farooqi later. “It’s something I think all Muslims are supposed to think about.”

I thought of my visit to Beaverdale Memorial Park, the secular cemetery, less than two weeks before. I had stood with Dan Krueger before the yawning grave — 36 inches wide, 8 feet long and 5 and a half feet deep, standard-issue size. The sides and bottom of the grave were perfectly flat, like the bottom of a big chest. Below my feet were 32,000 graves, people buried between 1929 and 2019, men, women, large and small, all stacked side by side in this resting place for the dead.

Looking at the grave, I had found it easy to think of death and burial as a strictly mechanical process. The excavator that digs the grave with its metal claws would belong just as much on a construction site or a scrapyard as in a cemetery.

But then I remembered what Bajwa told me.

“Death is a powerful, profound reminder on how you should live your life: You can live your life, be obsessed with your job, your career, accumulate power and prestige, but when you go to the grave … no wealth, power will go with you,” he said. “You were born into this world naked and you will go to the grave naked. And, at that moment, you will hear the fading footsteps of your loved ones. That is a moment of feeling profoundly alone.”