Looking back:

When Yale students couldn't vote

Last November, hundreds of Yale students and New Haven residents waited in line at City Hall in the hopes of registering to vote in the 2018 midterm elections. The hours-long wait forced many potential voters to give up on registration or be turned away, stirring up controversy about same-day registration in the Elm City.

But this was not the first time that registration workers managed a seemingly endless line of Yalies. In 1971, over 500 students queued half an hour before the registrar opened, attempting to vote in New Haven for the first time. Until a federal court’s ruling on Sept. 13 of that year — three days before the deadline to register to vote in a contentious mayoral primary — students in the city were effectively barred from participating in municipal elections.

Yale students were and still are separate from New Haven in more ways than one. As is true today, town and gown issues — such as Yale’s tax exemption and the University’s growing presence in the Elm City — played a defining role in local politics half a century ago.

While some things have not changed, today’s New Haven is markedly different. In 2019, the city is a Democratic stronghold — the Board of Alders has not had a Republican representative since 2011. But in the 1970s, the city, like the state, was relatively more conservative. In the 1972 and 1976 presidential elections, the Greater New Haven area voted for Republican candidates Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford, respectively.

Student enfranchisement became one among many democratizing forces in the politics of the time, challenging a conservative political machine and liberalizing the electoral process. Looking back, students’ legal fight for enfranchisement in the Elm City exemplifies how student activists have the power to enact real and sustained change in New Haven.

FROM THE CLASSROOM TO THE COURTHOUSE

In 1971, two Yale undergraduates enrolled in a course called “Law and Social Change” taught by Richard Abel. Before leaving campus, they wrote a final paper that catalyzed a series of court cases that ultimately gave Yale students the right to vote in the Elm City.

Joseph Rubin ’71 and Mark Lecinger ’71 did not plan on instigating the process that eventually took New Haven to court. But, when the pair learned that the city frequently refused to let Yale students register to vote on the basis of failed residency requirements, they interviewed dozens of graduate students — most of whom had been denied by the registrar — and wrote their final paper on the subject.

“We were only undergraduates, but we did some research on it, and it seemed to us that they [the city’s conservative political machine] didn’t want people with more liberal views registering to vote,” Rubin said in an interview with the News. Their decisions, Rubin continued, had “no rhyme or reason.”

With Abel’s help, they then took the paper to Yale Law’s Stephen Wizner, who ran one of the school’s legal clinics. In the months that followed, graduate students, Yale Law School professors and the Connecticut Civil Liberties Union combined their efforts to give Yalies the fundamental right to vote.

Rubin, who now serves as Assistant Deputy Attorney General in Connecticut, described the late 60’s and early 70’s as “a time of great social and political activism in New Haven and elsewhere.”

In 1969, the University welcomed the first women to Yale College, ending well over two centuries of single-sex undergraduate education. And two years later, Congress enfranchised 18-year-olds, responding to the Vietnam War-era argument: “old enough to fight, old enough to vote.”

The amendment became law on July 1, 1971, less than two months before Yale students would return to campus in the midst of a hotly contested mayoral election. The election — the first for which most students met the voting age requirement — would bring to light New Haven’s machine politics, the town and gown relationship and Yale students’ will to have a say in the Elm City. The legal fight for enfranchisement began with two dozen of those students.

THE INITIAL RULING

After Rubin and Lecinger brought their paper to Wizner, a clinic at the law school partnered with the Connecticut Civil Liberties Union to represent 24 student plaintiffs who sued the City of New Haven in federal court for denying them the right to register to vote.

On Sept. 13, 1971, Judge Joseph Blumenfeld ruled in favor of the plaintiffs. At the time, then-Secretary of State Gloria Schaffer deemed the case one of “national significance,” for it was the first time a federal court ruled on the issue of residency requirements for student voters.

The lawsuit charged the Elm City with discriminating against student voters by presuming students “not to reside at the place of their physical habitation” while not making the same presumption of other voters. Despite the fact that Yale students lived in New Haven for the majority of the year, the city did not regard them as permanent residents.

To vote in New Haven in 1971, applicants were required to be United States citizens, at least 18 years of age and city residents for at least six months. The plaintiffs claimed that the Board of Selectmen, New Haven’s voter registration authority, created excessively strict requirements for students, essentially preventing them from voting by forcing them to prove that they regard New Haven — and no other place — as their home.

The case, Kennedy v. Meskill, was originally brought before a three judge panel, as is required when challenging a state law, Connecticut’s definition of legal residency. Federal records of the case have since been destroyed, but the case is well-documented in newspapers from the time, and — through a series of interviews — the News has been able to reconstruct the narrative.

Early in the proceedings, the State of Connecticut determined that New Haven had been “misapplying the state [residency] statute,” and ceased its participation in the litigation, leaving the city to continue defending the case by itself. Immediately after this decision, two of the panel judges dropped the case, citing its local nature. This left the students’ fates in the hands of Judge Blumenfeld, who was nominated by President John F. Kennedy in 1961.

The students’ lawyers in the case included Richard Snyder, Eugene Sosnoff and Wizner, who is currently the William O. Douglas Clinical Professor Emeritus of Law at Yale Law School.

The case centered around the definition of permanent residency. Like most students, the plaintiffs possessed legal documents — such as drivers’ licenses and draft registrations — that used their parents’ addresses, and they often returned to their parents’ homes during academic breaks. The city argued that this made them transient residents and therefore undeserving of a say in municipal matters.

In an interview with the News, Wizner recalled a cross examination by Corporation Counsel Thomas Keyes Jr., the main lawyer representing the City. According to Wizner, Keyes asked each of the student witnesses to present their drivers’ licenses and requested that they read their listed addresses to the court.

In an interview with the News, Snyder recalled Blumenfeld’s warning to the counsel: “Mr. Keyes, you’re not a state trooper.”

In their redirection, the students’ lawyers asked whether the students intended to return to the addresses recorded on their licenses, to which they responded, “I don’t know.”

To Wizner and his team, the case boiled down to the legal concept of domicile — the place to which a person always plans to return. A person cannot have multiple domiciles, and because the students had no set plans to leave New Haven upon graduation, they were legally permanent residents, Wizner told the News.

In his final opinion, Judge Blumenfeld said that it appeared from the testimony that students “were subjected to a special line of inquiry,” including more extensive and discriminating questions than those asked of non-student applicants. He also noted that many rejected students had qualifications identical to those of non-students.

While the State of Connecticut did not issue an official position on the matter, then-Gov. Thomas Meskill expressed his opinion that students should vote in their parents’ hometowns. Then-Secretary of State Schaffer seems to have echoed this sentiment by ordering Connecticut towns to issue absentee ballots to college students, enabling students from the state to vote at home.

Ultimately, Judge Blumenfeld ruled in favor of the plaintiffs and ordered the City of New Haven to treat student applicants as it would any other prospective voters and to register the 24 plaintiffs as well as all others who met the deadline that Thursday.

THE ELM CITY’S REACTION

The ruling ignited a spirited debate in the Elm City. One resident submitted a letter to the New Haven Register accusing the ACLU of a “fishing expedition.” The author argued that by asking prospective student registrants to identify “anything out of the ordinary” in their registration processes, the organization was engaging in a “spurious, most unliberal attempt to entrap voter registration officials in wrong-doing.”

Another New Havener detailed a number of “considerations for the college voter” in a letter published in the Register. Chief among these was that “the privilege of voting, now as always, carries with it a wide variety of citizen obligations.” Judge Blumenfeld’s decision, the author continued, left questions surrounding these obligations — including jury duty, car registration and local property taxes — unsettled.

This letter touched on a theme central to the student voting debate and the impending mayoral primary: Yale itself.

Given the fraught town-gown relationship, Yale became a focal point of a contentious primary election, with incumbent Mayor Bartholemew Guida and the Democratic party organization linking his strongest challenger, “reformist” Democrat Henry Parker, with University interests. It was broadly believed that Yalies would support Parker — buses decorated with Parker stickers carried droves of students to the Hall of Records to register for the primary, and Yale English professor George Lord circulated a letter to his colleagues encouraging them to vote for the challenger.

Attorney Edward Reynolds, Guida’s campaign manager, told the Register that “the student voter movement is the end result of the ultra-liberal university community’s attempt to knock out Guida since he has taken Yale to task on the tax issue and sponsored zoning changes which restricted its land acquisition.”

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Yale was magnifying its presence in the city, buying more property on Chapel Street and planning to construct two new residential colleges — today’s Benjamin Franklin and Pauli Murray. As a consequence, the University reduced the proportion of city property eligible for taxation. Per the Connecticut Constitution, Yale enjoys a tax-exempt status and instead makes an annual voluntary payment to New Haven. Today, that payment amounts to about $11.5 million per year — only a $2.5 million increase from what Mayor Richard C. Lee requested in lieu of taxes fifty years ago. According to current Mayor Toni Harp, if Yale paid property taxes, it would owe the city $194 million today.

While the University’s fiscal relationship to the Elm City has always been a point of contention, it took on new meaning when Yale students gained the right to vote. This enfranchisement, many city residents and local politicians charged, was an instance of representation without taxation.

Candidates for the Board of Alders, New Haven’s legislative body, were among the most vocal objectors. Democratic Ward 23 candidate Stanley Rogers claimed that black property owners and tenants already pay the price for Yale’s tax immunity and that the University’s students, for all their support of lavish appropriations, “would not be around to pick up the tab for the heavy taxes that such programs would require.”

Joseph Carbone, chairman of Students for Guida, pointed his finger at Yale faculty, whom he charged with trying to dictate voting — and thereby exacerbate an already-burdensome taxation program — rather than trying to eliminate the University’s practice of free riding.

The rhetoric became, at times, quite heated. Samuel Kropp, Democratic candidate for Ward 28, contended that students are vocal in their demands but not in their offers to contribute to city finances. He also called their residency claims into question despite the federal court’s decision. If students are in fact residents of New Haven, he said, “their ability to make themselves invisible during the summer months should be patented.”

There was, however, another side to the debate surrounding residency and representation. As noted in a 1971 issue of the Yale Law Journal, the U.S. Census Bureau decided in 1950 to count students as college-town residents rather than as residents of their parents’ towns. This had significant implications for legislative apportionment that played out on the national stage — by 1964, 43 states included out-of-state students in their populations for apportionment purposes — as well as in the local arena.

In 1971, each of New Haven’s alders represented approximately 4,600 residents. Given that Ward 1 housed 3,800 Yale undergraduates, the alder for this ward represented only 800 bona fide, voting “residents.” As a result, Ward 1 residents enjoyed almost six times the voting power of residents of all other wards, which were populated by 4600 voters and no Yale students.

The issues were not clear cut, but there were clear sides. Students found allies in reformist Democrats who anticipated benefitting from their votes. Meanwhile, members of the party machine, including Mayor Guida himself, opposed potential enfranchisement. The debate over Yale students’ right to vote that was not just one about registration, but rather one over the role the University plays — and the one it ought to play — in the Elm City.

NEW HAVEN’S FAILED LEGAL RESPONSE

Following Judge Blumenthal’s initial ruling, the case was as unsettled as residents were.

On Wednesday, Sept. 15 — a day before the deadline to register to vote in the primary election — the City of New Haven appealed the decision to the U.S. Second Circuit Court of Appeals in New York. Corporation Counsel Thomas Keyes Jr. argued that federal courts do not have jurisdiction in local elections, citing the Supreme Court case U.S. v. Arizona, which established that 18-year-old voting provisions were constitutional and enforceable when pertaining to federal but not local elections.

His attempt fell flat almost immediately. The three-judge panel dismissed the case before hearing the ACLU’s rebuttal, leading Sosnoff to remark to the Register, “This must have been one of the shortest court sessions I have ever seen.”

Sosnoff was the only one of the students’ main lawyers to witness the session. In an interview with the News, Snyder reminisced about a delayed train that left him and Wizner “huffing and puffing and running into court” only to be told by the chief judge that their arguments would be unnecessary.

The two joined a defeated Keyes for their train ride back to New Haven.

The circuit court’s dismissal affirmed Judge Blumenfeld’s earlier decision that the Elm City could not ask student applicants any questions beyond those asked of all prospective voters. Keyes interpreted Blumenfeld’s ruling to mean that the registrar could ask detailed, personal questions to student applicants — provided that those same questions were also asked of everyone else.

On Wednesday morning, before the appeal was dismissed, Keyes had instructed the registrar to ask all prospective voters a list of 13 court-approved questions. At 2:40 p.m. that day, he doubled the list and required that the new questionnaire be administered on paper rather than orally.

In addition to 22 other queries, applicants were asked whether they regarded New Haven as their home, whether they had claimed any other addresses in the past six months, whether they or their spouse own a car registered or taxed in another city, and where they are registered for the draft, if applicable.

According to Keyes, even if a student regarded New Haven as their home, they were not entitled to vote if any of their other responses indicated ties to a different jurisdiction. The Yale students and their lawyers criticized Keyes’ questionnaire as inconsistent with the spirit of the law.

“The questionnaire is unreasonable and is burdensome on the registration process,” Sosnoff told the Register in 1971. “Further, it operates as an English literacy test and hurts groups like Spanish-speaking people.”

Keyes, defending his 26 questions, told the News at the time, “We have never quarrelled with the contention that anyone who makes New Haven his home for six months or longer is entitled to vote. These questions are simply designed to find out whether this is permanent residence or not.”

TROUBLE AT THE POLLS

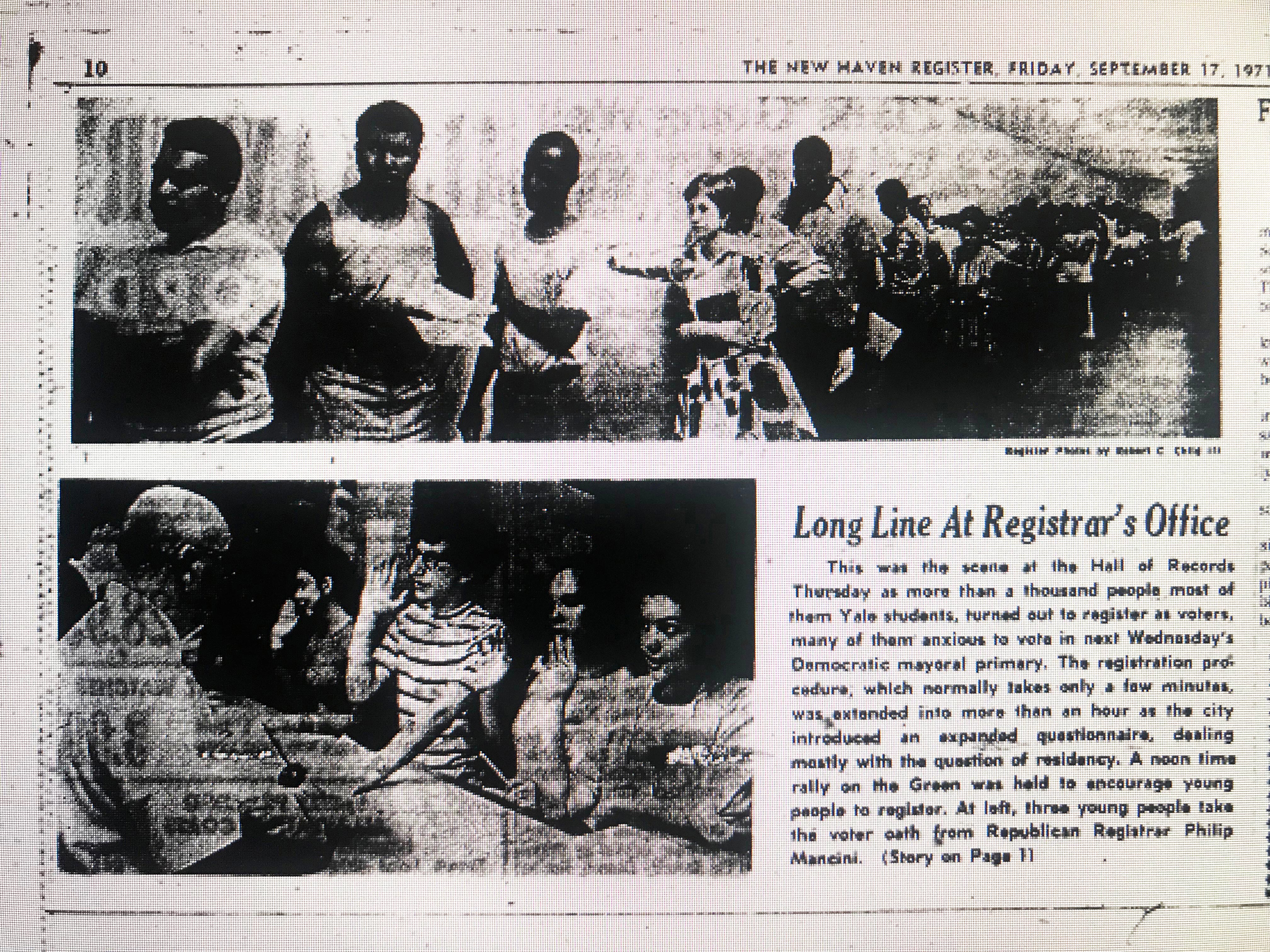

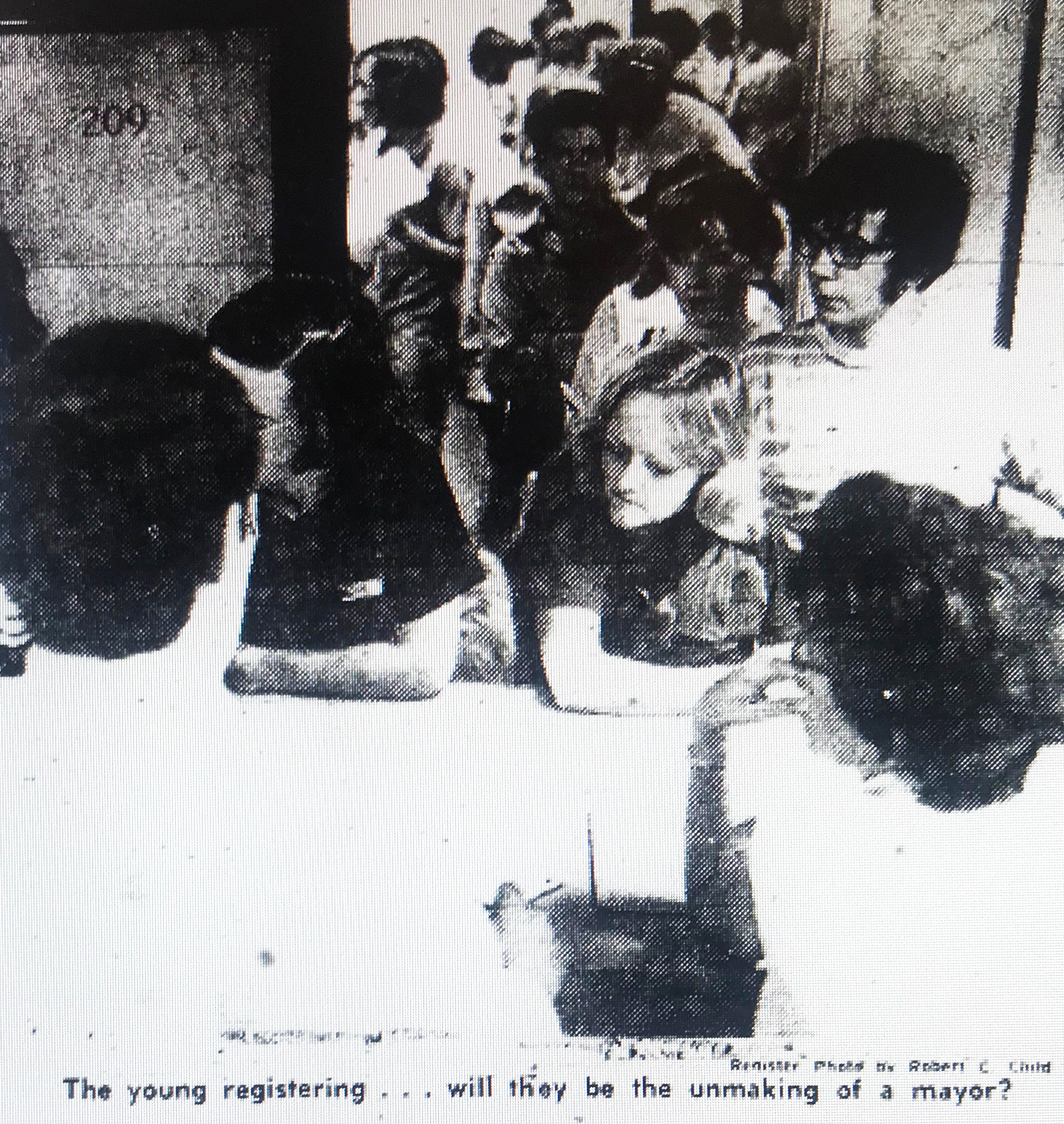

At the very least, Sosnoff was correct about one thing. The questionnaire was undoubtedly burdensome, increasing the time to process a registration application from mere minutes to over an hour. With a line that began forming outside the Hall of Records half an hour before it opened on Sept. 16, 1971, the registration deadline, this time increase was significant.

Progressive candidate Parker’s backers claimed that Keyes drew up the questionnaire to harass prospective student voters. Registrar workers responded with a similar accusation.

“It’s the Parker workers,” a Board of Selectmen spokesperson told the Register at the time. “They’ve disrupted our attempts to help people, they’ve called the ladies here MFers, and then they charge us with harassment.”

More than 1,000 new voters registered on Thursday, and more than half of them were Yale students. On Sept. 21 — just one day before the primary — over 100 students received notices informing them that their applications had been called into question on the basis of failed residency requirements. Deputy Town Clerk Sal Franco told the News that the Board of Selectmen invited applicants with only a driver’s license from outside of New Haven to return for further questioning, but outright rejected those applicants with both a driver’s license and draft registration outside of the Elm City. Of the 114 invited to return, 56 showed up on election day and were added to voter rolls.

Those 56 voters were a minority among their peers. Five-hundred-nineteen students who met Blumenthal’s qualification standards attempted to register; of these, 309 — or 59 percent — were rejected. Only 32 of the more than 1,000 non-student applicants met a similar fate.

The students’ lawyers criticized the city for engaging in illegal disenfranchisement. Eighty-one percent of rejected students were turned down on the grounds of out-of-state drivers’ licenses, while more than half of similarly situated non-students were accepted. Blumenthal’s opinion had specifically ruled out drivers’ licenses as a permissible justification for rejection.

“The procedures read like a Southern voting case with blacks in the early 1960’s,” Sosnoff told the Register. “They were clearly discriminating against students.”

The plaintiffs’ legal team charged the Elm City with contempt and moved for supplementary relief. They sought to compel the city to allow students who had been denied registration to vote after the polls closed. That day, Federal District Court Judge Robert Zampano signed an order directing the City of New Haven to provide reasons why it should not be charged with contempt of Judge Blumenfeld’s order, which required the city to register students who demonstrated a clear intent to reside in New Haven. A hearing for the issue was set for Sept. 30.

THE PRIMARY AND THE MACHINE

In the meantime, New Haven witnessed the end of a fierce three-way contest for the city’s top office. The 1971 race featured incumbent Mayor Bartholemew Guida and his two challengers, community organizer Parker and labor leader Vincent Sirabella. Guida, who emerged victorious, remarked that the primary was unlike anything he’d experienced in his 35 years of political life.

In essence, it was a competition between reform Democrats — led by Parker — and the party establishment. Guida’s administration had been marred by scandal and his challengers liberally used words like “graft,” “corruption,” and “bossism” to describe his tenure. In the general election, Republican candidate Paul Capra would decry the mayor and Democratic Town Committee chairman Arthur T. Barbieri as the “Barbeiri-Guida Machine.”

Guida ran on his prior record of preventing the collapse of urban renewal programs sponsored by the federal government and managing a volatile political environment in the Elm City. He also cited efforts to address the “nagging problem of what to do about large tax-exempt institutions in our midst which receive all the essential municipal and protective services without contributing their fair share towards the cost of that service,” clearly referring to the University.

Parker, who finished second to Guida in the 1969 mayoral contest, built his campaign around four key issues — economic development, education, Yale’s role as a “city within a city” and taxation — as well as voter registration efforts. His campaign registered nearly 5,000 voters in advance of the primary election.

Guida’s campaign also pushed for voter registration, but unlike Parker, it did not concentrate on the recent additions to New Haven’s electorate.

“If we don’t [turn out]” Guida’s campaign manager warned, “the university-student movement may, ironically, teach New Haveners their first lesson in the politics of the 1970s.”

Indeed, Parker was the clear favorite among Yale students and faculty, and managed to flip Ward 1, which houses the majority of the University campus. Just two years earlier, he lost the ward and the primary to the Mayor. While Parker did not go on to win the day in 1971, reform Democrats captured 11 seats on the Board of Alders.

The relationship between Guida’s campaign rhetoric, the Elm City’s machine politics and the Board of Selectmen’s rejection of student applications was not lost on Wizner.

“They [the selectmen] seem to be thinking, ‘let’s win the election and then worry about the judge’s order,’ which is disgraceful,” Wizner told the News.

THE PUBLIC DEBATE CONTINUES

The Sept. 30 proceedings did not go the students’ way and their motion for contempt was denied, according to the court docket. As such, no student votes were added to the election totals. However, even if they had been, Guida’s margin of victory was too broad for the student vote to have made a difference.

The court did, however, affirm that the Board of Selectmen was prohibited from rejecting any of the plaintiffs or similarly-situated applicants except upon “clear and convincing evidence of non-residency.” With the primary election in the past, the students turned their attention to an Oct. 9 deadline to register to vote in the 1971 general election on Nov. 2.

In response to a letter published in the New Haven Register encouraging students to vote in their hometowns, graduate student Joseph Minarik submitted his own letter criticizing the “paternalistic attitude of college town people for students, which can best be expressed as ‘we’ll take your money in our stores and for rent, but try to vote.’”

The original letter, entitled “Should Vote Absentee,” expressed a fear that college voters would upset the “political balance” of the Elm City. In repudiation, Minarik cited a Supreme Court ruling that disenfranchising segments of the population based on how they may vote is unconstitutional.

A MAYORAL RACE IS DECIDED — THE COURT CASE ISN’T

The debate, rampant in city newspapers, also continued in the courtroom.

After several hours of litigation on Oct. 6, Judge Blumenfeld ruled that the proceedings — which focused on the 26-question form — had become “too repetitious.” He ordered the plaintiffs to return only when they had collected all the facts.

Wizner and Charles Kleinberg GRD ’72, a third-year graduate student, drew up a summary on Oct. 7. Kleinberg told the News that they were trying to prove “a systematic bias, or any type of bias” against prospective student voters. They specifically cited the case of two Jonathan Edwards students, both of whom had out-of-state drivers’ licenses, out-of-state parents and Jonathan Edwards College recorded as their New Haven address. One of these students was able to register for the primary election, while the other was not.

Fifty-nine percent of qualified student applicants were rejected, as compared to less than three percent of non-students. New Haven’s Board of Selectmen judged the majority of rejected student applicants by standards — specifically, out-of-state drivers’ licenses — which were ruled illegal in September.

Neither the News’ nor the Register’s articles indicate that students experienced significant difficulties in registering for the general election. The general was also marked by increased voter mobilization efforts as students and city officials organized registration drives on Yale’s campus and throughout the Elm City.

The race featured Guida and Republican Paul Capra, who criticized, among many things, the Guida administration’s “lackluster” efforts to tax currently exempt property like that of the University.

Guida did, however, meet with members of the Yale Corporation in October to discuss the University’s financial relationship with the Elm City. At the meeting — the first of its kind since 1937 — Yale administrators acknowledged that tax exemption poses a legitimate financial problem for New Haven and Guida urged the institution to “recognize [its] responsibilities to the urban center in which [it is] located.”

Parker, the overwhelming Yale student favorite in the primary, endorsed Capra. The Republican hopeful called on young people, including Yale students, to make their voices heard in the general election.

“The big question facing us at this moment is whether the [26th] amendment is merely a paper tiger — a bone thrown to the wind in the hopes it will go unused,” he said at a campaign rally. “The majority of legislators who passed this amendment are undoubtedly certain that youth will register and participate in no greater numbers than the majority of their elders, who are content to let the few do the job of the many.”

Ultimately, this call to action was not enough. Guida handily won the election by a margin of 5,815 votes, and the Democrats gained five seats on the Board of Alders. Fifteen minutes after polls closed, a disappointed Capra sighed and whispered, “They’re unbeatable.”

Guida would go on to serve another two terms as mayor until, in 1975, the New Haven Democratic machine took a hit with the election of reformist Frank Logue, who served as mayor of the Elm City from 1976 to 1979. Guida died by apparent suicide in 1978.

THE RIGHT TO VOTE, SECURED

Kennedy v. Meskill was finally closed on April 28, 1972 — 228 days after the initial ruling.

The same year, the Supreme Court ruled that durational residency requirements — like New Haven’s six-month requirement — violate the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection clause. Six years later, the Supreme Court ruled that denying students the presumption of residency afforded to other prospective voters violates the Constitution.

This year marked the 24th mayoral primary in which Yale students were eligible to cast a ballot. In 1971, over 500 students attempted to become New Haven voters in the three days between the court’s initial ruling and the registration deadline for the fiercely contested primary election.

In contrast, a mere 106 people voted in Ward 1 last Tuesday for this year’s tight race between Mayor Toni Harp and progressive challenger Justin Elicker SOM ’10 FES ’10. Ward 1 is the only district which has an overwhelming Yale-student majority as it encompasses eight of Yale’s fourteen residential colleges, as well as Old Campus.

Yale students’ right to vote is the culmination of a hard-fought legal struggle. Nearly 50 years have passed since Rubin and Lecinger originally interviewed Yale students who were denied that right. Theirs was a simple idea: New Haven students are New Haven citizens.

Editor’s Note: Research for this article was primarily conducted via Yale Daily News and New Haven Register archives from 1971. News archives have been digitized and are published online through the Sterling Memorial Library. New Haven Register archives can be accessed on microfilm at the New Haven Free Public Library. Court records of Kennedy v. Meskill have been destroyed, but a limited docket is available via the Federal Records Center.