UP CLOSE:

Playing the last hand

On the evening of April 6, Yale alumni came from far and wide to celebrate the Asian American Students Alliance’s 50th anniversary.

But just moments into University President Peter Salovey’s opening remarks, a mass of 80 students walked silently into the room carrying a banner that read “Ethnic Studies is our studies.” Alumni rose from their chairs and revealed their own signs that read “We stand with ethnic studies.” Members of the audience began to pepper Salovey with questions: Why had the demands surrounding the Ethnicity, Race and Migration program not already been met? When would the University “solve the problem[s]” facing ethnic studies?

To some recent alumni in the room, the event struck similarities with one that had occurred just four years ago, when members of Next Yale — a group formed in the wake of a series of racial controversies in the 2015–2016 academic school year — found themselves face to face with Salovey. The group had formulated a list of demands in November of that year and submitted them to the president. The first on the list — the “immediate promotion of the Ethnicity, Race and Migration program to departmental status.”

In response, Salovey finally gave the ER&M program the power to recruit scholars for four faculty slots especially designated for ethnic studies.

Since its inception as an undergraduate major in 1997, ER&M has become one of the fastest growing programs. But despite its popularity among undergraduates, the administration has frequently restricted the interdisciplinary program’s ability to hire, tenure and recruit faculty members. Four years ago, eight years ago, 11 years ago, 17 years ago and 22 years ago, faculty members’ predecessors as well as the campus’s students faced battle after battle. And finally, the professors — perched behind countless calls for more — dealt their last card.

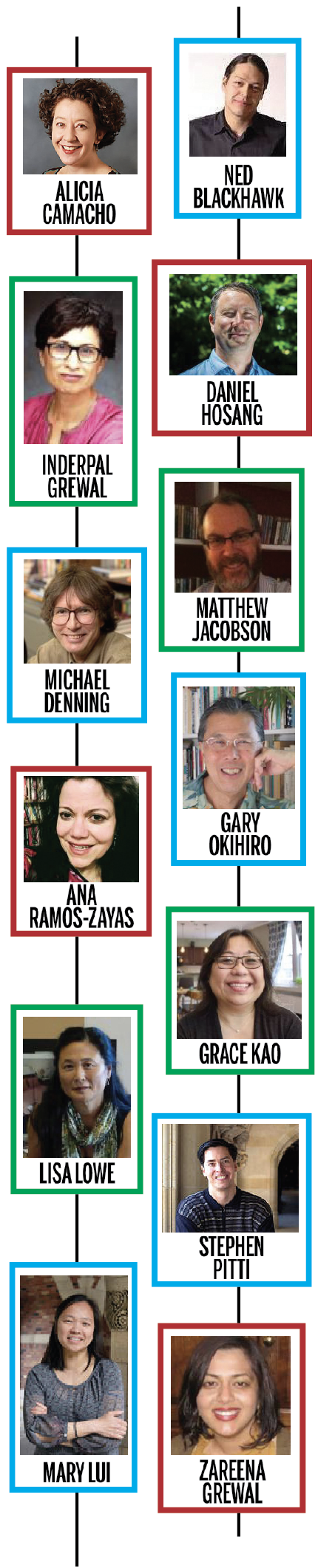

On March 29, 13 professors — including four endowed chairs, two heads of residential colleges and four current department or program chairs — informed Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences Tamar Gendler of their “intention to withdraw their labor” from the ER&M program.

“If the University decides it does not want to take that action, the future of the program would be in doubt,” associate professor of American studies Daniel HoSang, one of the 13 faculty members, told the News. “If the University does not take action, the program will die off.”

A MYSTERIOUS PROCESS

In the 1990s, a group of students designed a syllabus for an advanced Asian American studies course and asked American studies and English professor Michael Denning — who knew very little about the field at the time — to teach the seminar.

“This was one of the groups of Yale students who was more interested in the shape of their education than most Yale students that I had encountered,” Denning recalled.

He said that from the outset, undergraduates like these had been a driving force in developing Yale’s ER&M program.

According to Denning, efforts to develop an ethnic studies curriculum came to fruition in the 1990s. Yale College decided on six classes — two in Mexican American studies, two in Asian American studies and two in Puerto Rican studies — to be taught under the umbrella of the American Studies Program and set out to recruit part-time faculty members to teach the ethnic studies courses.

Denning said the scholars hired to teach the courses were often paid little, and he “felt embarrassed” asking faculty members from established universities in cities like New York to take the position. As interest grew, ethnic studies looked to hire more professors in the field, which remained the program’s primary objective from 1992 until 1997.

The University moved toward the next step of establishing more formalized professorships, but Denning and his colleagues were cognizant that recruiting and retaining faculty members would be difficult. Since ethnic studies did not yet have a major or a program formally associated with it, the discipline relied on appointments from neighboring fields — ranging from history to religious studies — to fill positions.

By 1997, ethnic studies had momentum. Scholars in the field had successfully attained University funding to bring in more faculty members through the years, and students began to petition for a major. Once approved, the University offered ER&M as a double major, meaning that interested students would have to couple it with another degree.

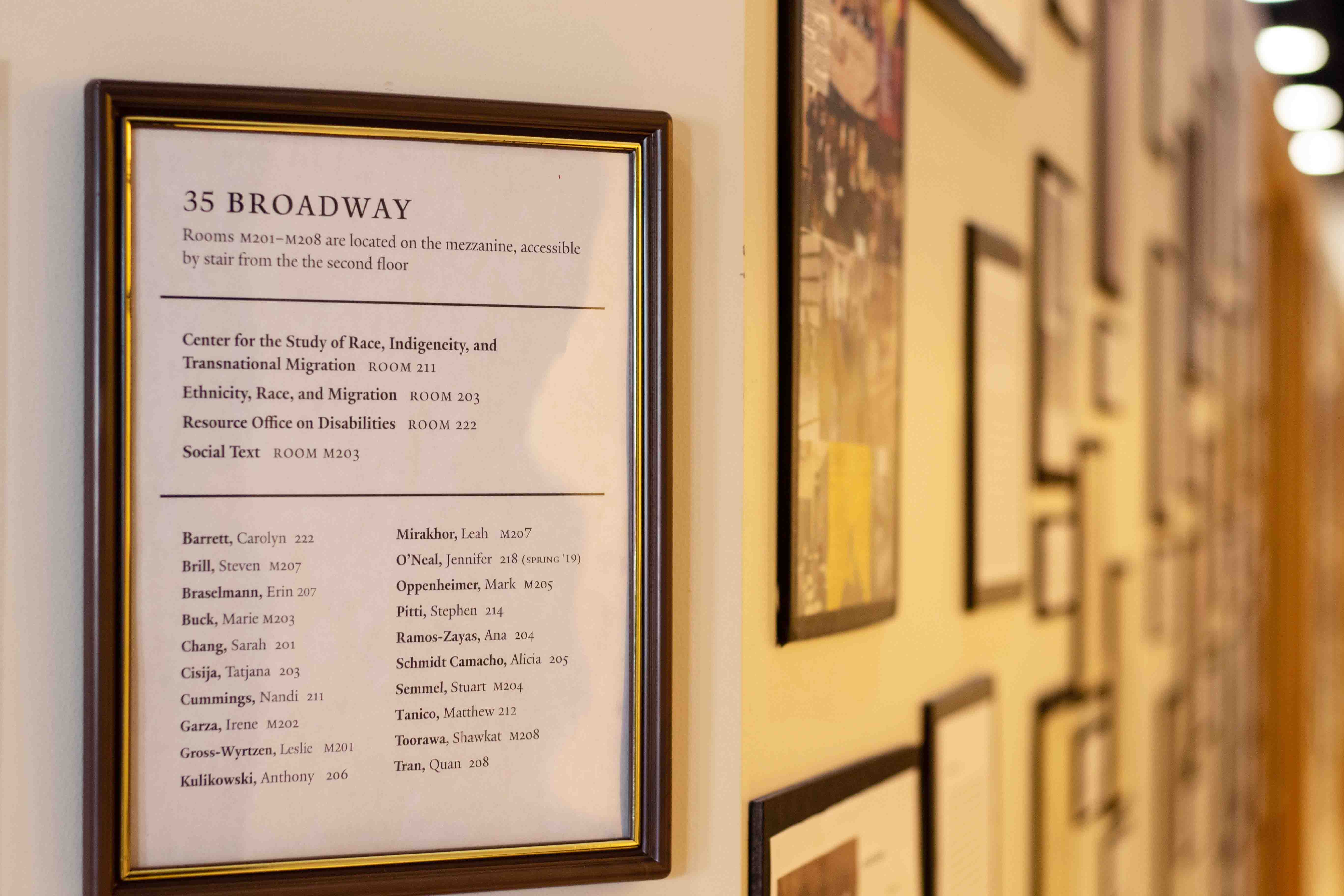

In those early years, ER&M housed itself in the MacMillan Center both “physically” and “institutionally,” according to Denning. But it soon became clear that ER&M required more space. They moved to 35 Broadway St., tucked behind the shops on York Street, where the program remains to this day. But the status of ER&M on campus remained in flux despite these developments.

“There are very clear ways about how you make a major,” Denning said. “How you create a program … is a much more mysterious process, and that requires long conversations with provosts and presidents and people who make decisions about hiring.”

THE LONG FIGHT

HoSang, an ER&M faculty member, and Ana Ramos-Zayas, professor of American studies, Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, and director of undergraduate studies for ER&M, entered Yale in the 2017–2018 academic year. According to the advertisement for their positions, their appointments would be made jointly through ER&M and “another fitting academic department or program.” They were to be the first hires specifically recruited with faculty lines in ER&M, a commitment made in the wake of the 2015 student protests.

Alongside the guarantee of the four ER&M faculty lines following 2015 activism, the University established the Center for the Study of Race, Indigeneity, and Transnational Migration and guaranteed the allocation of $50 million over five years to recruit and retain diverse faculty members. Yuni Chang ’18 and other members of Next Yale considered the changes, specifically the creation of the RITM, as successes.

It was in the context of the 2015–16 student protests that faculty members and administrators launched into a renewed set of conversations on an old set of topics. Following the protests and the University’s commitments, faculty members still remained unclear as to what the closed-door negotiations had yielded.

“Yale did not honor those demands because we’re asking for the same stuff now, and it’s only three years later,” Chang told the News. “The University is lying about what it’s doing on this issue, or it has deluded itself into believing it is supporting ER&M and its faculty.”

Since 2002, faculty members in the program have requested enhanced powers for ER&M, including oversight over faculty appointments and the ability to develop courses in ethnic studies. In 2008 and 2011, faculty members met behind closed doors with administrators to push for increased support for the program. According to Denning, the administration’s response to many of these meetings aligned with “the administration’s response to lots of things”— faculty members were assured that they were heard and that the University would investigate their concerns.

ER&M became a standalone major in 2012, by which point it had an increased number of faculty members associated with it. But some issues — including attainment of faculty lines, a commitment to a unit or field of study that allows that entity to search for and hire ladder faculty members — did not immediately change.

Last academic year, the University commissioned an external review of the American Studies Program and commissioned a group of visiting scholars in February to provide guidance on American Studies. According to HoSang, external reviewers explained to him that the faculty dean’s office informed them that neither his appointment nor that of Ramos-Zayas resided in ER&M.

HoSang was subsequently provided with documents that effectively showed that ER&M had no faculty slots.

“It’s a sign when the faculty members themselves are unclear about the nature of their appointments about a sort of institutional disregard,” HoSang said. “The intention was to appoint us in ER&M, but even if we have appointments there, it’s only 50 percent. … It’s inaccurate to say two appointments have been made to ER&M.”

The revelation that HoSang and Ramos-Zayas did not have formal appointments in ER&M in University documents left HoSang and other faculty members confused as to where their appointments truly lied.

In an email to the News, Gendler explained that Ramos-Zayas and HoSang are listed in a variety of official University documents — including their letters of appointment and the Yale College Program of Study — as being ER&M faculty members.

She said ER&M does, in fact, have four faculty slots, adding that this is twice the number of slots assigned to the interdisciplinary Program of Cognitive Science. Units like ER&M and cognitive science rely on faculty members associated with other departments and programs, according to Gendler. These slots provide the program hiring power, but according to Gendler, ER&M, like many other units, share these hiring powers with other programs or departments. This means these units may search for faculty members who have existing full appointments in other units, while others make external joint appointments.

“Nearly a third of the searches that we conduct every year are joint searches between two or more units: This is in no way unusual in the faculty,” Gendler said.

Still, Gendler said that Workday — a University-wide computer system which stores faculty records and manages payroll and other finance operations — “unfortunately” did not have an option to list faculty members as ER&M.

She explained that when the university converted to using Workday, “hundreds of thousands” of adjustments had to be made and clerical errors were inevitable. According to Gendler, this is the only such location in which the faculty members are not formally recognized for their appointments in ER&M.

“Faculty associated with the program were not recorded in that way in [Workday], or in documents that we generated on the basis of that system,” Gendler wrote in an email to the News. “We are grateful that professors in the program have alerted us to this simple anomalous bookkeeping oversight, and we are adding a node for ER&M so that their appointments can be recorded appropriately.”

Gendler said that by July 1, when the new appointment season begins, her office will ensure that “these appointments are recorded appropriately.”

Denning said he hoped this inconsistency was a misunderstanding surrounding the program’s faculty appointments.

“That’s one thing where I agree with [Salovey] entirely,” Denning said, referencing Salovey’s remarks that he had thought the matter of faculty lines in ER&M had been worked out by 2016. “It seemed to a lot us that we had worked these things out. … He thought it was all worked out. We thought it was all worked out. But it turned out that it wasn’t.”

THE CATALYST

In 2018, the Program of American Studies announced on its website that its Director of Undergraduate Studies Albert Laguna had received “yet another book award” for “Diversión,” his widely acclaimed work employing popular culture to examine the Cuban diaspora. His program unanimously approved him, promoting him to the next stage of the tenure review process under the humanities Tenure Appointments Committee — composed of a group of professors across various units within the humanities.

But to many of his colleagues’ suprise, the humanities Tenure Appointments Committee denied Laguna tenure. The specifics of tenure cases are confidential. Dean of the Humanities and chair of the tenure committee Amy Hungerford told the News that four women and two faculty members of color have worked on the committee, which lists 13 members on its website. According to Hungerford, the committee pulls its members from a variety of intellectual areas, taking into account factors such as the professors’ disciplines and geographical focuses. The committee — which will hear approximately 25 to 30 cases this year according to Hungerford — assesses a range of factors in evaluating cases, including the candidate’s scholarship, letters from experts in their field and course evaluations.

Gary Okihiro — visiting professor of American studies who has helped shape a variety of ethnic studies programs at peer institutions such as Columbia University and Cornell University — said that universities nationwide view ethnic studies with great skepticism. He said that universities use the discipline as “fire insurance” — a way for universities to diversify their faculty while protecting themselves against student protests and negative publicity.

To many representatives from the Coalition for Ethnic Studies at Yale, Laguna’s tenure denial was the catalyst behind their movement. In just two months, the group, which held its first organizing meeting in February, garnered over 1,000 followers on Facebook and spearheaded activist efforts across campus — from banners reading “Protect Ethnic Studies Faculty” to a pop-up library honoring the works of the 55 ER&M faculty members who have left the program since its founding.

But faculty members and students interviewed by the News were careful to note that the frustration that ultimately led to the current activism surrounding the ER&M program began far before the start of this semester, Laguna’s tenure denial and the questions prompted by faculty administrative documents. For many, the impetus behind the withdrawal was a gradual buildup of frustration regarding the continuous decline of the program’s ability to function.

According to HoSang, as the number of undergraduate ER&M majors has increased, the number of faculty members with appointments in ER&M has effectively declined in recent years. HoSang and Ramos-Zayas both added their labor to the program in the 2017–2018 academic school year, but three faculty members left ER&M in that timeframe, according to HoSang. The model of the program, which borrows labor from faculty members across the University, is not sustainable given the growing student interest in the program, Hosang added.

Though he was on leave this past fall, HoSang said that he found himself on campus every week in order to meet with undergraduates due to a lack of faculty advisors in the program. As he looked ahead to the 2019 semester, HoSang knew his workload — which includes research, teaching and administrative requirements — would only worsen in the months ahead.

“We’ve long known that these issues were making our situation increasingly precarious,” HoSang said. “I felt like I would be misrepresenting our capacity and the status of our program by suggesting that it was something that it was not.”

A PATTERN

Birgit Rasmussen, a former assistant professor in American studies and Ethnicity, Race and Migration at Yale, came to the University in 2009, and she understood that her appointment would be 50 percent American studies and 50 percent ER&M. When she went up for promotion to associate professor — an intermediary step which has since been abolished in the new tenure system — her colleagues in American studies promoted her for consideration under the Tenure Appointments Committee in what her colleagues later told her was a unanimous decision.

Still, she, like Laguna, was denied tenure by the committee.

Rasmussen, who left the University in 2016 and currently works as an associate professor of English at Binghamton University, stressed that her specific experience was not necessarily important on its own.

“It’s easy to dismiss me and then potentially dismiss the whole thing,” Rasmussen said. “For me, what matters here is that there’s a real pattern, and the pattern is a shame.”

She expressed solidarity with Laguna, stating that although the denial of tenure can be “devastating, both professionally and emotionally,” she knows he “is an outstanding scholar [who] will do well.”

Two other former professors, Guillermo Irizarry and Jason Cortes, recalled positive experiences within the ER&M program. But because of the locations of their appointments, the Department of Spanish and Portuguese had oversight over their tenure and promotion cases. Hostilities within the department left them feeling disadvantaged in the tenure review process. Both professors departed from the University, Irizarry before facing the tenure review process and Cortes after his contract was not renewed. Cortes said that the ER&M program’s lack of involvement in the tenure process provided the unit with no ability to protect the scholars’ positions within the University.

Iritzarry’s decision to leave the University before facing the tenure review process is not uncommon. Lillian Guerra, who began at the University in 2004 as an assistant professor of history, said she often had to prove to her colleagues the merit of her research on the modern Caribbean and, more specifically, Cuba. According to Guerra, a senior faculty member frequently told her that the “little country” of Cuba had a predictable future and past. Guerra said colleagues often encouraged her to focus on a larger country and described her specialization as “nonessential.” According to Guerra, another professor in the department referred to her as “Maria” for several years.

“You have an intellectual economy that has been driven by racial assumptions about the value of certain cultures and the value of certain histories — what is a grand narrative that is institutionalized and monumentalized at Yale,” Guerra said. “It’s bigger than [racism]. It’s imperial. It’s driven by theories of what is good and what is bad, what is relevant and what isn’t.”

While she battled with members of her department belittling her work, Guerra received an offer from another university. She weighed her options — uprooting to a completely new institution or remaining in what she described as a hostile environment. Guerra ultimately chose to leave Yale in 2010, tired of trying to defend herself and her scholarship, as she said she had done from the moment she arrived on Yale’s campus.

Guerra, now a tenured Cuban and Caribbean history professor at the University of Florida, said that she regrets the choice to leave the University and believes it would have been hard for Yale to refute the value of her scholarship in the tenure review process had she chosen to face it.

“How much impact do I make [at the University of Florida], and how much impact would I have made [at Yale]?” Guerra asked. “The impact that you make for the same amount of effort in a place that is automatically resourced is much greater. It’s a political defeat that I have accepted that, unfortunately, I am responsible for.”

All five professors formerly associated with Yale’s ER&M program interviewed by the News said they respected the 13 faculty members’ decisions to withdraw their support from the program. They represent just a fraction of the professors who have left ER&M since its founding.

And at the end of next academic year, this number will grow by at least one. Inderpal Grewal — professor of American studies and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies — will retire. She has been at the University for 10 years.

“I was a little tired of struggling against a lot of forces here at Yale,” Grewal said of her decision to retire.

THE FUTURE OF ETHNIC STUDIES

When the News reached out to Guerra to discuss her former experience with the University, she sent back a reply expressing various frustrations with the Yale administration and her department. Still, in spite of all the “negative stuff” about Yale, she expressed admiration for her dedicated students.

“They are also Yale,” she said.

Irene Vázquez ’21 declared herself an ER&M major in April 2018. She was halfway through with the major by her sophomore fall, and she discovered a community within the program, including faculty members and her best friend and roommate. But according to the 13 faculty members’ press release, while junior and senior majors will receive advisory support, first years and sophomores are not guaranteed the same. Now, Vázquez is unsure whether she will be able to major in the program.

After the faculty members announced their “intention to withdraw their labor” from the program, she recalls walking to her class, looking around and realizing that there are students on campus who can “just spend their time studying” unburdened by concern for the institutional issues on campus. The privilege, she said, spans a variety of mediums — including income level and race — and for Vázquez, added onto the stifling environment of Yale is now the mental bandwidth of constantly thinking about her intended program of study, what it has given her and what its future may or may not look like.

Vázquez — who organizes with the Coalition for Ethnic Studies at Yale and raises awareness for ER&M across publications like Broad Recognition, a feminist publication on campus — says that in this political moment, the stakes are incredibly high for ethnic studies.

“I kind of hate the phrase ‘now more than ever we need ethnic studies.’ But now more than ever, we need ethnic studies,” Vázquez said. “We’ve always needed ethnic studies, it’s just particularly visible now as to why.”

Janis Jin ’20, who also organizes with the Coalition for Ethnic Studies at Yale, said she is pushing for ER&M’s survival — the program that made her recognize the ways in which Yale’s exploitation of its faculty members of color is connected to “imperial power, colonialism and racism at home and abroad” — beyond her time at Yale.

Like Next Yale, the Coalition for Ethnic Studies is demanding that ER&M become a freestanding department. But Salovey, when confronted by over 100 alumni and students protesting his speech at a gala dinner earlier this month, hinted that departmentalization of ER&M was not likely. Instead, he expressed a desire for the unit to remain a program, but with expanded power over hiring.

“The study of race, ethnicity, migration, and indigeneity is a central part of Yale’s mission of education, scholarship, and research,” Salovey wrote in an email to the News. “University leadership shares the view of our faculty colleagues that the ER&M program needs appropriate recognition of its status as a distinct and vital area of study, with commensurate appointing rights. I am committed to ensuring that Yale will be a leader in research on these topics and in supporting a vibrant intellectual environment for teaching and learning in this area.”

But, according to HoSang, the 13 professors understand that changes regarding the status of ER&M would likely need to come from the faculty dean’s office. For this reason, the faculty members submitted their individual letters of withdrawal from ER&M to Gendler. They did not enumerate a specific list of demands.

“We don’t create the structures,” HoSang said. “The administration does.”

Gendler told the News that the external review of the American Studies Program — the same one that informed HoSang and Ramos-Zayas of the ambiguity surrounding their appointments — should be completed before the end of the term.

According to Gendler, the findings will inform decisions regarding the best structure for ER&M at Yale.

“Yale has a long history of supporting work in the areas of race and ethnicity,” Gendler wrote to the News.

Faculty members with past or present associations with the program — who have either left the University or withdrew their labor from ER&M — generally refrained from explicitly demanding a department. Most simply cited the need for increased control over hiring as well as more influence in the tenure process, including the ability to narrate cases to the Tenure Appointments Committee and to present external letters of recommendation. But for some, the future of ER&M at Yale has implications far beyond the University walls. Many stressed that Yale should serve as an example for peers and institutions across the country.

HoSang told the News that the interest exhibited by both students and faculty members in ER&M during his time at Yale has exceeded his expectations. HoSang said he hopes his students — the juniors and seniors who will finish with degrees in ER&M as well as the sophomores and first years who may not be able to — know that the decision to withdraw his labor did not come from disregard for the students or a lack of dedication to the discipline. The current model, he said, had simply become impossible.

“Yale could have such a profound role to play in modeling what a unit like this could look like,” HoSang said. “And I hope it doesn’t miss the opportunity to do that.”