UP CLOSE:

"Crime is decreasing" — rhetoric or reality?

When William Outlaw III was released from prison in 2008 after two decades behind bars, the New Haven he returned to was not as different as he had hoped.

He still witnessed a great deal of “neighborhood versus neighborhood” violence among youth. For example, if youth from Newhallville area were in a fight youth in the Fair Haven area, the whole Newhallville neighborhood would have the same attitude: “We don’t like them and so on sight, we are going to shoot or fight.”

Aged 13 to 25, members of the groups would be “fighting and jumping” at each other, which led people to start picking up guns, Outlaw said. Even those not deeply involved with the conflict feared attack because of association. Sometimes, even groups from two different streets in the same neighborhood would fall into conflict. Disputes resulting in violence would erupt “on sight, day and night,” Outlaw remembered.

Now, Outlaw sees a changing New Haven. He does not see interneighborhood violence erupt in the street. Crime in New Haven still occurs, but its nature has shifted — and its rates have decreased.

Today, as a New Haven street outreach worker who mentors youth, Outlaw is glad to be playing a role in the reduction of violence throughout the city.

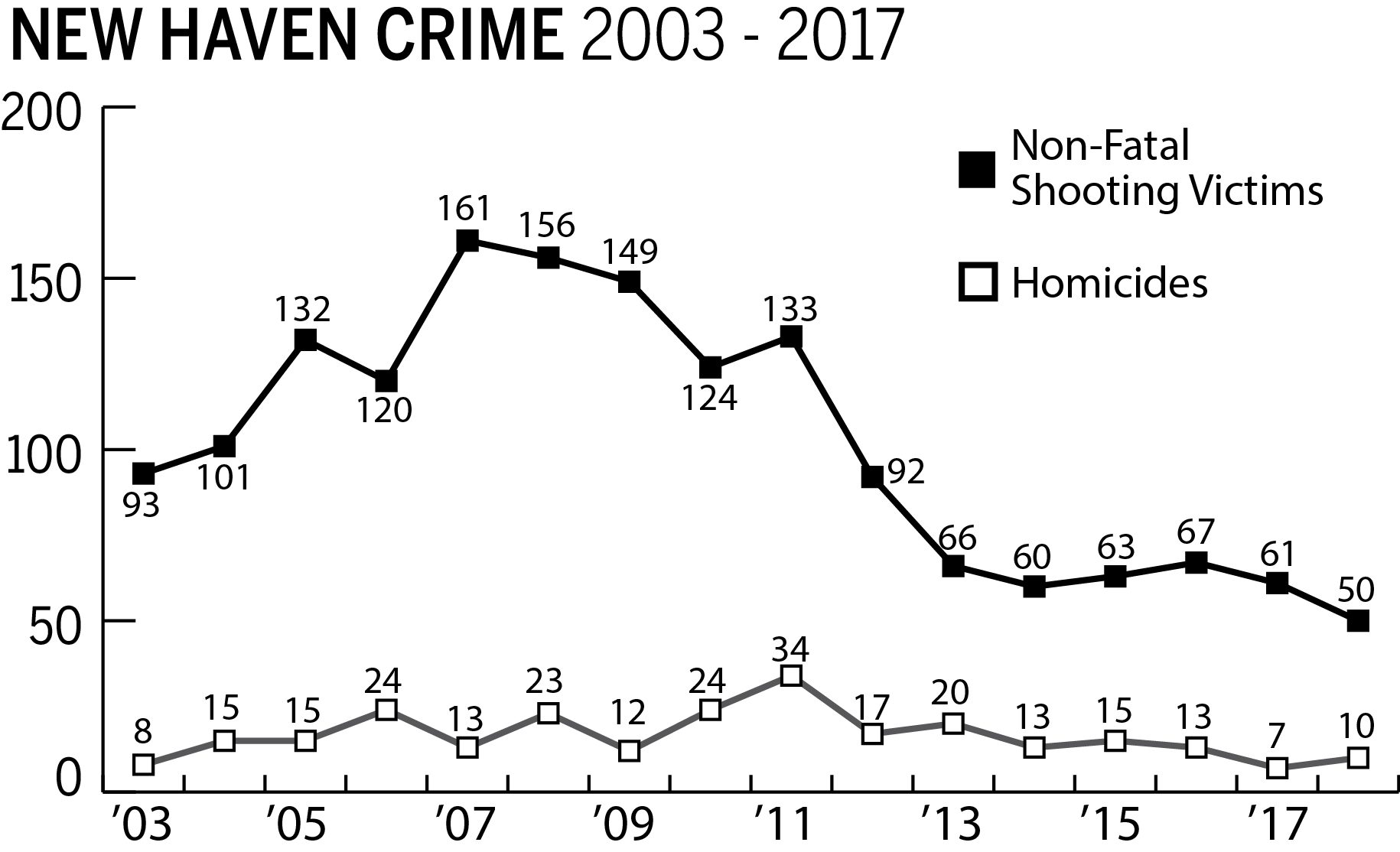

Violent crime in New Haven has been steadily marching down for the past decade. With 156 gun assaults reported in 2008 and 50 in 2018, many agencies and individuals in New Haven are jumping to take credit for the significant decrease. But crime reduction is markedly more complex. The News spoke to 19 New Haven residents to understand the forces behind the changing face of crime in the Elm City. From a changing policing strategy, to a changing culture, to a changing collective will — what is the reality behind the statistics, and what is driving the change?

THIS CAN’T GO ON

For decades, the Elm City has grappled with a reputation for violent crime. In 1991, The New York Times published an article headlined “Armed Youths Turn New Haven Into a Battleground,” describing a “crisis in the streets” — spurred on by the gun and drug trades, gang culture and turf battles claimed the lives of many teenagers. The city saw 15 homicides in the first three weeks of May that year.

“Without a question, we’re worn out from grief,” local Rev. Robert Newman told the Times in 1991.

Steve Hamm, a police reporter for the New Haven Register from 1983 to 1986 who is currently working on a documentary about New Haven community policing, said that when he reported on crime in the 1980s, he could hear gunshots from his reporting hub on Long Wharf. Often, he was able to get to the scene even before an ambulance arrived.

In the early 2010s, the Elm City continued to experience high crime rates. New Haven made headlines in 2011 when Business Insider named it the “fourth most dangerous” city in the United States. New Haven reported 15.8 violent crimes per 1,000 people — ranking fourth following St. Louis, Missouri, Detroit, Michigan and Flint, Michigan, based on preliminary FBI data.

Leonard Jahad, director of the New Haven Street Outreach Worker Program — a team of four that forms close relationships with youth and stages interventions to prevent crime — remembers 2011 as the year the city went “bonkers.” That year, New Haven saw a decade-high homicide rate: 34 homicides, 10 more than the year prior. Crime was a problem, and it became a dominating political issue in the city.

“So many people were shot that year — and there were funerals going all summer long in New Haven — and I think that the community was just revolted by it,” Director of the Connecticut Statistical Analysis Center Ivan Kuzyk told the News. “Internally, people just said this can’t go on.”

And it didn’t. Though the road the city has traveled has not been easy or straightforward, things have, on the whole, changed.

YOU CAN FEEL THE CHANGE

Like Outlaw, residents in and around New Haven interviewed by the News agreed that the city feels safer than it did a decade ago — and commended actors working on reducing crime in the area.

Jahad emphasized that the presence of gangs and gang violence in the community is “way, way, way down,” noting that most of the murders that have occurred in the past few years are those related to personal issues rather than to street gang violence.

Hamden city councilman Justin Farmer, who lives on the border line between Hamden and New Haven, said that six years ago, he lived next to drug dealers. Now, most of his neighboring homes are occupied by new homeowners or by first-time family renters. Just a few years ago, his neighborhood could see as many homicides in a year as the entire city of New Haven did in 2018.

“It feels almost surreal because I still see petty drug dealers all the time, but I don’t see [them] to the same extent that I used to see. I used to see dime bags all the time,” Farmer said. Still, he added that he sees fluctuations — a few months ago, he saw a bag with crack in his neighborhood for the first time in years.

And the statistics concur.

This January, former New Haven Police Chief Anthony Campbell ’95 DIV ’09 stood in front of an audience of officers and community members at the NHPD headquarters to present a summary of last year’s crime numbers. Plastered on the walls behind him were large-scale prints of bar graphs and tables representing nonfatal shooting victims and homicides. Sorted by year from 2003 to 2018, they all presented a general downward trend in citywide crime, from shootings to aggravated batteries.

“On many of these charts, you’ll see a significant drop in our crime — not just violent crime but quality-of-life crimes, including robberies and burglary, are down,” Campbell announced. “When you walk around this city, you can feel the change.”

The statistics showed a reduction in nonfatal shooting cases over the decade. From 2003 to 2006, New Haven saw an average of 111.5 nonfatal shooting victims, while between 2007 and 2010, the average was 147.5. From 2011 to 2014, the average nonfatal shooting rate decreased to 87.75, and then further decreased by 2018 to 60.25. There were a reported 426 shots fired in 2011, 229 in 2013, 105 in 2015 and 134 in 2017. Campbell pointed out that the city’s 10 murders in 2018 were nowhere near its 34 homicides in 2011.

“Five years ago, halfway through the first month of my first term as mayor, I had already been to a funeral for a New Haven teenager — the victim of gun violence that was all too common at the time,” Mayor Toni Harp said at the press conference. “Today I stand before you … to describe a much improved New Haven, a much safer New Haven, a city much better equipped to quash the scourge of gun violence.”

At the press conference, things seemed to be looking up. But what exactly has changed in the Elm City? And who is responsible?

MANDATED COMMUNICATION

In the past few years, the New Haven Police Department has attempted new methods to improve its policing and reduce crime in the Elm City.

Every Thursday at 10 a.m., dozens pile into a fourth-floor room at the NHPD headquarters for COMPSTAT — the weekly crime information–sharing meeting that began in 2012. Sitting side by side at desks in a two-layered U-formation, NHPD officers, unit heads, local department members and community program leaders share information about the crimes committed in the past week. One by one, representatives give updates about crime from institutions including the Department of Corrections, Yale New Haven Hospital and the Traffic and Parking Department.

At each meeting, eight NHPD district managers — lieutenants who oversee at least one of the city’s 10 policing districts — present crime data and trends over the last week, flashing graphs up on a screen that show weekly comparisons of individual crimes, such as robbery, aggravated assault and firearm discharge. After each district manager presents, anyone in the room has the chance to ask questions.

At the April 4 meeting, a district manager reported a shooting near Alpha Delta Pizza on April 1 and noted that he had immediately increased police presence and extended officer hours in the area. Another district manager informed his peers that in the area of a shooting at an apartment complex, 15 street lights were out — the officers made sure the light bulbs would be replaced.

“Bridgeport, Hartford are trying to do [COMPSTAT] like what we do, and they’re not really doing it. That’s why their numbers are higher than ours,” Jahad said. “All these similarly situated cities, their numbers are higher. They aren’t talking.”

Lieutenant Karl Jacobson — the NHPD officer in charge of the shooting task force, Drug Enforcement Administration task force, narcotics enforcement unit and criminal intel unit — told the News that law enforcement operated in silos prior to COMPSTAT in 2012 and the daily Intel meetings in 2013. He said it was kind of a “do your-own-thing” process, with some people even fighting for cases or hiding things from each other.

Now, communication is mandated. Different stakeholders in the crime reduction process must show up to the meetings and share information. And unlike most cities, New Haven’s COMPSTAT is open to the public.

Jacobson said that the NHPD “turned a corner” when they began communicating through COMPSTAT and daily intel meetings, as well as working more with federal partners on projects and investigations. He noted that the NHPD takes crime stats, and overlays them with intelligence coming in through informants, anonymous tips and interviews, adding that the department gets “a ton” of information from the State Department of Corrections.

The reduction in crime, however, is not just a function of city efforts to improve communication. On the street, there has been a substantive shift in the culture of crime.

A NEW ATMOSPHERE

Now — rather than neighborhood versus neighborhood gang activity — Outlaw describes the new atmosphere of violent crime in the city as a few “hot pockets” where individuals incite violence against other individuals for personal reasons.

With this changing atmosphere, city officials and community members looking to reduce crime have had to adapt their methods to better reflect the state of the city.

New Haven Youth Services Director Jason Bartlett told the News that when Mayor Toni Harp took office, she made youth the priority. Harp’s philosophy says that by re-engaging youth and reaching out to neighborhoods, crime will reduce, Bartlett said.

“Really identifying kids who might be the victims or perpetrators of crimes and trying to help them overcome obstacles, giving them interventions, wraparound services — it makes a big difference in terms of crime,” he added.

One example? New Haven’s Street Outreach Worker Program, which was established in 2007.

The program’s four outreach workers — some of whom have been involved with crime and turned their lives around — form personal connections with youth and intervene in disputes with the potential to become violence.

In the past, outreach workers would often wait on street corners for violence to erupt. Now, in light of the changing atmosphere, the outreach workers monitor social media. Once an outreach worker catches wind of the potential for violence, they will reach out to involved individuals to talk through the issue.

“Don’t make this a neighborhood thing,” Outlaw, a street outreach worker, would tell them over a personal meeting or lunch.

For Outlaw, working on crime reduction as a street outreach worker in New Haven is a 24-hour job. Beyond one-time interventions, he ensures continuous communication between those who need help. He gets the kids’ numbers and calls them constantly — “What’s up? How you doing? What’s going on?” He wants to talk with them not just about the worst times, but also about the “good times, the bad times and the times in between.”

On a Thursday in April, Jahad, Outlaw and Tommy, a high school sophomore whose name has been changed to protect his privacy, sat clustered at one edge of an otherwise empty 20-seat conference table at an office on Grand Avenue. Tommy was having a hard time and reached out to Jahad for mentorship.

The meeting marked Tommy’s official introduction to Outlaw. At their 8 a.m. meeting, the three spoke about Tommy’s family life, social life and school experience — and then the outreach workers gave him advice about joining a basketball team, finding a job and staying in school.

As Tommy stood to leave the meeting, he exchanged phone numbers with Outlaw — they planned to stay in touch. Outlaw said he will try to speak with and learn as much about Tommy as he can — “so that he won’t turn that corner.”

As he left the meeting to make it to school on time, Tommy told the News that he was going to find a job.

ARE WE POLICING BETTER?

Jacobson stressed that it is “amazing” that New Haven’s crime has stayed consistently low, even while the violent crime numbers for Bridgeport and Hartford — nearby cities with similar population sizes and demographics to New Haven — have gone up.

According to their respective police department’s numbers, Bridgeport’s non-fatal shooting rate has been on a steady incline from 2017 — increasing from 70 shootings in 2011 to 111 in 2017. Hartford’s non-fatal shooting rate has fluctuated from 116 in 2011, down to 97 in 2014, and peaking to 123 in 2016.

“We used to have the same [crime numbers] as them…. So we’re obviously doing something different,” Jacobson told the News, adding that 50 shootings in New Haven is still a lot considering the size of New Haven’s population.

Jacobson, like others interviewed by the News, attributed crime rate reductions to Project Longevity — a collaboration between law enforcement, community representatives and social service providers to stop gun violence in Hartford, Bridgeport and New Haven. According to Project Longevity’s website, in addition to providing a range of services to youth and promoting messages about their value in the community, the program also communicates a clear message that “the next group to commit homicide, or the most violent group overall, will be met with the full force of the law and all of their group members will receive focused attention from members of local, state, and federal law enforcement.”

Jacobson also noted that the NHPD also follows up with personally-driven shooting incidents. He added that high numbers are driven by the logic: “I shoot at you, and then you shoot at me. But he’s my boy, so he shoots at your people, and they shoot at his people.”

In these personal incidents, either members from community programs like the street outreach workers will intervene, or the NHPD will employ the use of probation and parole.

At daily intel meetings, shooting victims are displayed on a screen, allowing other officers to point out if the victim is on probation.

“So, yes, he’s a victim, but he’s probably going to retaliate. We don’t want to victimize a victim, but we are going to put him on GPS and make him stay home until he gets a job. Or make him limit the area that he’s traveling so that he doesn’t get shot again,” Jacobson said.

He said that the first few times, the “guys get mad at you,” but then they see the solution “for what it really is” and sometimes thank him. After a month or two, the NHPD takes the victims off GPS monitoring, he added.

“Now what does that do? They didn’t get involved with the beef, they didn’t get arrested, and now they move on and get off probation. It’s the best tactic possible,” Jacobson said.

AN OUTSIZED EFFECT

Though local actors are working to decrease crime in New Haven, broader forces are shifting the landscape of crime in the Elm City.

Kuzyk runs the the State’s criminal justice research unit for the Office of Policy and Management, conducting statistical studies on Connecticut crime, courts and prison systems. In his sixties now, Kuzyk has studied crime in the state for decades.

“It’s kind of odd to talk about Connecticut,” Kuzyk told the News, explaining how the state has a handful of small cities that are generally poor and have scored lower on negative social indicators. These cities carry a disproportionate amount of reported state crime and a disproportionate number of residents who are dragged into the criminal justice system.

According to the FBI Uniform Crime Report, Connecticut saw 78 murders in 2016, while Bridgeport, Hartford and New Haven combined saw 38 homicides. Approximately half of the state’s homicides were committed in those three cities, which comprise just 11 percent of Connecticut’s population.

Within any one of these cities, a few people have “sort of an outsized effect,” Kuzyk said. With violent crime caused by a disproportionately small number of people, it is difficult to compare New Haven to state or even national trends.

Nationally, violent crime rates are decreasing — a fact many New Haven residents noted to the News. According to FBI data, the national number of reported violent crimes per 100,000 people has decreased by approximately 49 percent from 1993 to 2017.

“[The NHPD] act like they’re doing something special. No, it’s been decreasing for years, across the nation,” New Haven activist and community leader Barbara Fair told the News.

Kuzyk noted that “each community is like a “retail sort of situation,” and that there are many factors specific to each city that affect the crime rate — including political will, policing strategy and community programs. However, Kuzyk mentioned a major factor that is reducing crime: collective behavior. He has noticed that people’s behavior has shifted over time, and that even though there is no tangible way of quantifying and assessing it, “behavior is really everything behind shootings.”

“A neighborhood can be exactly the same, the community is the same — but something is different,” Kuzyk said. “There’s no data on behavior. So where you don’t have data on behavior, everyone is sort of able to fill in between the lines with how they want to explain what happened.”

Kuzyk also emphasized the changing urban drug market and culture from the 1990s and the early 2000s to today.

He described drug markets of the past as being reliant on geography — people were getting killed because drug dealers needed territory to be selling drugs. They needed to hold “corners.” But cell phones have basically killed that. Now, transactions can happen anywhere and are not tied geographically. Kuzyk said many drug dealers have two cellphones — one personal and one for drug transactions. Every time the latter phone rings, that person will make $50. So, Kuzyk said, when the dealer goes to prison, he can sell the phone to his competitor or friend for $30,000.

The drug market of today no longer reflects the geographic necessity of holding corners. Though it is impossible to quantify the effect this changing drug market has had on crime rates, Kuzyk noted that if much of the violence a decade or two ago was related to drug markets, and those drug markets have changed dramatically in the past decade — then it would follow that the amount of crime has changed dramatically as well.

“What’s happening is society is changing, behavior is changing, the markets are changing, the nature of criminality is changing,” he said.

Jahad echoed Kuzyk’s sentiments.

“[The street outreach workers] changed our strategy because before we’d hang out more on the streets before things would happen,” Jahad said. “A lot of drug dealing on the curbs in certain pockets. Now, people don’t sell drugs on the street anymore. They’ll text someone, they’ll [direct message]. That’s stopped a lot of street violence.”

In addition to natural changes in the market and community programs, federal officials have worked with with local law enforcement agencies to conduct sweeps, taking some gangs and violent groups off the streets.

In 2011, the FBI and NHPD did a joint investigation into the city gang Grape Street Crips, and charged 18 individuals, according to a 2015 FBI press release. The identified leaders of Grape Street Crips were sentenced to 188 months in prison for “heading a gang-related narcotics distribution ring,” the press release stated.

In 2012, DEA agents, NHPD and Hamden police officers carried out an year-long investigation called Operation Bloodline, breaking up much of the Tre Bloods gang and charging more than 100 individuals. The joint investigation targeted drug trafficking and gang violence, with agents wiretapping telephones and conducting “extensive physical surveillance,” according to the U.S Attorney’s Office for the District of Connecticut.

In 2016, there was a sweep of the Red Side Guerilla Brims. And the following year, there was another sweep of the Goodrich Street Boys — a Newhallville-based gang — which was responsible for approximately 40 percent of the shootings that year, according to Jacobson.

“I gotta give the feds credit recently, they didn’t just go and arrest lower-level people. They were getting the right people,” Jahad said.

Despite the local and federal actions taken to address crime, a more complicated reality persists.

SUCCESS HAS A THOUSAND FATHERS

Fair, the local activist, said that it bothers her when the police “want to take all the credit” for crime decreasing, when there are many factors that bring crime down.

“It’s a scripted thing to say: ‘Crime is down. Look how great we are,’” Fair said.

Kuzyk described this dilemma to the News with an aphorism: “Success has a thousand fathers, and failure’s an orphan.”

Pointing to the New Haven data, Kuzyk highlighted that in 2016 there were 13 homicides, and in 2017, there were seven, a 50 percent drop. Yet, he is skeptical about assigning credit or blame for a drop of that magnitude.

“You know, I would have a hard time to say that reflects policing,” Kuzyk told the News. “Because the next year it goes up to 10. So, if you’re going to take credit for the drop between 13 and seven, then who takes the blame for when it goes up to 10 again?”

Kuzyk finds it unreasonable to think that there is “one silver bullet.”

To add to this distortion, Fair said that homicide numbers are often used to illustrate crime.

“Then they’ll report on murders — okay, there are two less murders than there were last year,” Fair said. “But how many shootings have there been? Is that success because the people didn’t die?”

Even Jacobson of the NHPD acknowledged this fact, saying that many victim’s lives are saved in hospitals such as Yale New Haven— they may not have been saved somewhere else like Hartford.

Fair said it is harmful for communities that continue experiencing high crime rates to continually hear officials touting that crime is down.

“[Those communities] feel like they are excluded when people talk about crime going down, because they hear gunshots every night,” Fair said.

She also noted that if you look around the city, there are parts of the community that can say crime is decreasing, while other parts remain more neglected, “so to stand publicly and say everything is better, that’s hurtful,” Fair said.

Outlaw employed a metaphor for explaining what he believes to be the reason behind the citywide crime decrease. If it were a piece of pie, Outlaw said, he would give the NHPD 70 percent of the credit, and 30 percent to other city initiatives, such as Project Longevity and the Street Outreach Worker Program.

“People like myself who were once a problem in the neighborhood, or created violence or destructed communities, I think we should have a role in fixing this program,” Outlaw said.

To fully understand the forces decreasing crime, one must look from the macro-level of shifting drug markets and collective behavior, to the micro-level of the individual interventions. New Haven has changed as a city, and along with it over time, so has the nature of crime.

Still, the 50 non-fatal shootings and 10 homicides that New Haven saw in 2018 are too many — a point many city residents acknowledged.

Outlaw told the News that with the reputation he built before prison — involved in violent drug operations and tried four times in New Haven for violence — gives him an in into the community. The respect he commanded in the past — he still feels it. But it is a different kind of respect now.

“Back then I wasn’t helping my community, I was destroying my community,” Outlaw said. “But now, they see help, they see hope.”