Stained, Lacquered, Checkered: Elihu and I in Chennai

Yale traded slaves in my father’s hometown. Where does that leave me?

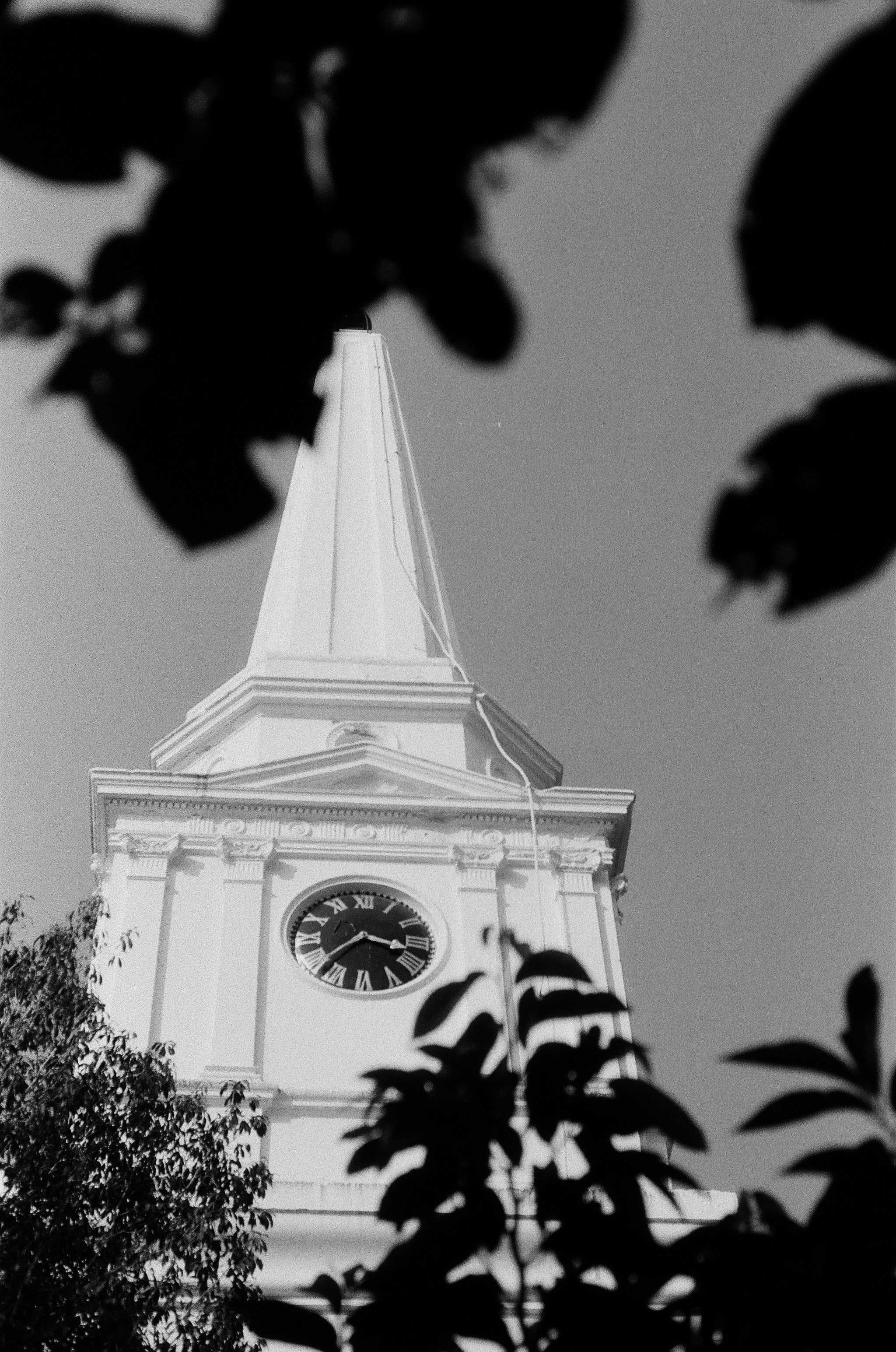

St. Mary’s Church is stained a clean white that balances out the blues and greens of the landscape. Nothing in the building’s architecture suggests how close it is to the Hindu temples 15 minutes away, let alone to the dark-skinned people that frequent such establishments. It seems to try to exist independent of its circumstances. The pews are wicker-laced benches, a typical product of South India. In the living room of my grandfather’s house 15 minutes away, we sit on similar wood benches. They were my grandmother’s. If I were to trace my lineage back in time, past the limits of our family records, I might find myself standing alongside a woman whose nose resembles my father’s, in the year 1680. It was then that the church held its first marriage ceremony — for Elihu Yale.

The church is one of the oldest British building in India. During the height of the East India Company’s empire, British subjects commonly referred to it as the “Westminster Abbey of the East.” Yale was one in a string of governors to be married in this church. But the brown congregation members I speak to don’t remember any of these weddings. In fact, they tell me they see the namesake of Yale University as just another unremarkable figure in what can only be named a fraught history. People do not like to revel in their history because no narrative can make sense of what happened here. The people I speak to here like to say that it is colonization, and then move on. We do not discuss the centuries of domination. Often I am told it is more helpful to look to the future, if not the present. Wallowing does not help anyone, says the church pastor here. They believe there the future holds hope, I think. They have to.

When we first stumble into the church, I hear my father curse under his breath. Like most of Chennai — the capital of Tamil Nadu, India’s southernmost state — it is swathed in sultry air. Crowds of dark-skinned people move back and forth on dated motorcycles and Vespas on a neighboring street. In the throng of skin, my father and I stick out as light, drawing stares. My father is with me partially as my escort: He grew up here and speaks Tamil fluently. But he’s also here because of what I’ve been telling him about Yale, about what was done to our people. He is no fan of religion, and certainly no fan of a religion meant as a proxy for imperial governance.

The air here has the same moisture and thickness as the air in St. James Parish Church in Montego Bay, Jamaica. The rafters are just as grand as those in Tan Dinh Church in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. These are both places my father and I have travelled to together, trying to understand the messy world we live in. Wandering past this church’s threshold, his eyes widen. But I don’t see what is immediately evident to him, to anyone who grew up in the open wounds of colonization, who knows “British” as a bad word like the back of their hand.

The pastor is an older woman with a sari under her white gown. She asks my father and me if we are Christian. No, says my father, I am from here. Her dark hair is tied up in a bun that is decorated with jasmine flowers. I can smell the fragrance following the wind as I chat with her after service. When she talks to me, I can’t help but wonder if this is how my grandmother, Vijaya, might look if she were alive. I wonder if this is how she would treat me, with soft oiled palms. And then I wonder about her mother.

When I press the pastor about Yale, she does not seem to know whom I am talking about. I say, he was the governor of Fort St. George, which draws a short pause. She takes my hand and directs me to a marble plaque with Yale’s name on it. In her office, set in a water-stained frame, is a small engraving of him. I think it’s all we have.

Thank you, I say. I come back here many times during my stay in Chennai. The walls: some white, some now stained a sulfuric yellow.

—

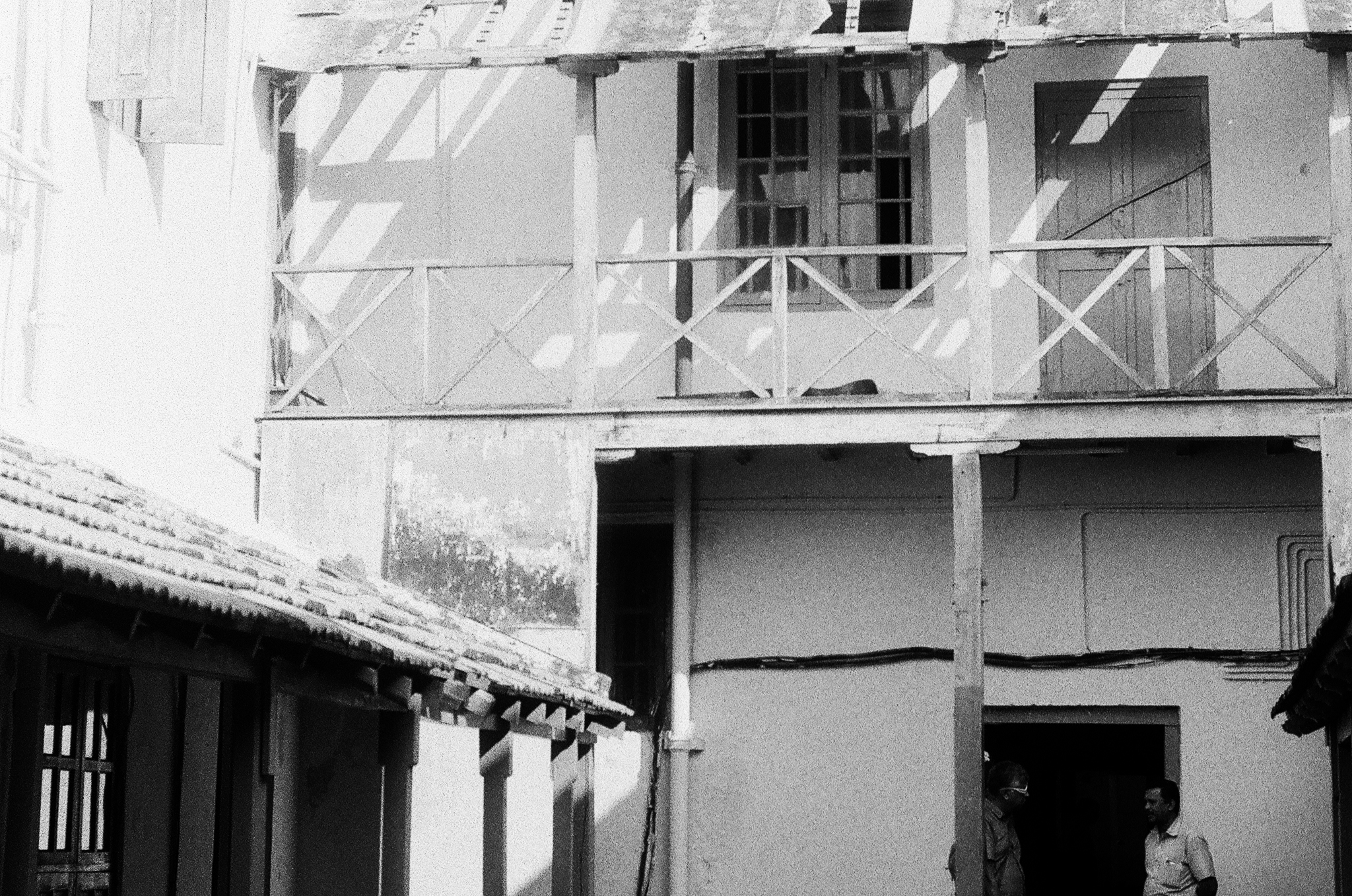

The Tamil Nadu Archives are painted a brilliant sienna. When I see the outlines of the red and white arches beyond the gate, I stop to take some photographs. Later, I learn, this design was made in the Indo-Saracenic architectural style, meant to reference the Islamic architecture for which India is traditionally known. But no Saracenic buildings were commissioned by brown voices or brown hands; instead, the revival style was used by the British during the period of the British Raj.

The library itself is practically open air, shelves saturated with dark pages, some of which are laminated, others imposed on cotton. The librarian who helps me mentions how the archive was severely understaffed because there wasn’t enough government money. Looking through 300-year-old pages, I see the toll that lack of money takes on preserving history. The archive is stacked with books on the Indian Ocean slave trade, books that Yale’s Orbis Library Catalogue has never heard of. The librarians who worked there didn’t seem to know why I was there. I kept telling myself that I did, that I knew what I was walking into. I didn’t. I still don’t really understand what happened there. I am still trying to clarify the facts.

Yale served as the governor of Fort St. George, now known as Chennai, from 1687 to 1692.

As I understand it, Fort St. George was a part of a larger network of stations in the Global South that was central to the British commercial venture. We had natural resources, and so they used us. We had people who could work, and so they took them. The truth is that I have written and rewritten this piece praying it will expose itself, crystallize or evaporate, like a bedside glass of water. It won’t.

—

During shopping period, I looked for a class on the Indian Ocean slave trade. If I couldn’t teach myself, maybe someone else could. There wasn’t one. The world does not offer the Indian Ocean slave trade the attention it requires, despite the fact that it enslaved many people. This disregard towards the region is often called the “tyranny of the Atlantic.” Despite growing up in the wake of the Indian Ocean slave trade, my father didn’t know anything about it.

When reading, I learned that many of those kidnapped and sold were African, and, according to scholar Richard B. Allen, “tens, if not hundreds, of thousands of slaves were exported from India and Southeast Asia …”

In lieu of the class I wanted, I am taking a class I need, called “Mobile South Asians and the Global Legal Order” with professor Rohit De. The class is mostly about South Asians and indentured servitude, another overlooked topic. One day, I approached him after class. I knew the Indian Ocean trade was different from the Atlantic, but the Atlantic was all that I knew, all that I grew up learning about. Could he explain?

He started by explaining major differences between the Atlantic and Indian Ocean trades. First, the slave trade in the Indian Ocean was associated with a pre-existing trade in the region in which enslaved individuals primarily performed household and domestic labor. Further, slavery in the Company was usually a result of “debt bondage” in which families sold their children to the Company to address debt.

De left the room in a flurry, and I thought of all those spare moments when he had reoriented the little knowledge I had. As one of the few South Asians teaching in the humanities at Yale, he is very valued by the brown community. Very valued, and thus, very busy. He told me to reach out to Tiraana Bains, YGS ’21, a past student of his.

I posed the same questions to her. “There were several forms of slavery … the kind that involved the purchase and sale of local people from South Asia itself, especially during times of famine …, the transport of enslaved Africans brought from West Africa to St. Helena and then to Madras or from East Africa and Madagascar via Bombay … many of these slaves found their way to English, later British settlements in Southeast Asia, which was in itself also a source of traffic in slaves.” What she said was starting to match what I was learning in De’s class. Though marginal, I had found the corner pieces of my people’s history. I knew a lot of histories. But I didn’t know the history my father would have called his own, had he been taught it. If I wanted to build a picture from the corners, I would need edges.

Edges, like the flush grass in Chennai, daffodils decorating the bottom of the picture: Those who were sold “had no way of escaping the situation they [were] in,” said De. But then I am lacking the colors of the sky, the architecture; I am missing the faces in the puzzle where I know people are supposed to be.

Professor Jay Gitlin, the associate director for the Howard R. Lamar Center for the Study of Frontiers and Borders, wrote in an email that “scholars have not fully investigated the trans-Saharan and Indian Ocean slave trades. They should.” So I have been told that I must build my own canon, start my own section in the library. But how much are we expected to build before we grow weary?

I learn many things in Chennai. At the Fort St. George Museum, amid pearlescent, peacock blue walls, I learn that the slave trade was moderated by the East India Company. A stained-brown map shows that the EIC divided Chennai into “White-town” and “Black-town.” “Black-town” compromised the entire city outside of the fort’s walls and was populated by the native peoples, who were commonly referred to as “black” in the EIC’s records. I can’t help but think of every story my mother had told me about how happy my father’s extended family was when they met her; you’re so white, they said. Yale was responsible for the fortification of said dividing walls even though the Company objected, was responsible for driving the separation of these communities into the physical soil, according to East India Company records in Manuscript and Archives.

The archive teaches me that the EIC relied on local slaves from the beginning of their time in the subcontinent. As in, looking down on people who are smaller and browner than you isn’t new. When I first get off the flight from the U.S., my dad and I meet a couple from Belgium. Excitedly, the woman mentions that they have seen a slum already. I know the real India, she says to me. As in, she wants to teach me. As in, I want to retch. Mostly, from the jetlag, or because of the flash of images that jolt through my head.

Local scholarship tells us that teenagers were often sold as slaves in the market. At one point, it was common practice for slave traders to kidnap children away from their parents. Those taken and shipped to other colonies — including Sumatra, Indonesia, the “East Indies” and Southeast Asia — were joined by individuals condemned by the EIC to hard labor in lieu of capital punishment. While many Company records in the Tamil Nadu Archive press the point that Madrasis often “sold themselves” into slavery, records show that this argument was usually a “defensive trick played by the slave traders to justify their greedy activities.” The community’s desperation was made worse by famines, which became more common as the British transitioned the community into commercial farming.

In 1683, the slave trade of Madras was supposedly abolished by Governor William Gyfford because of outcry from the local community. However, the fine associated with breaking the law was so small that the trade continued, unaffected. In fact, the Madras slave trade peaked in the 1680s. By the end of 17th century, the Madras slave trade, which was regulated by the Company, had increased in volume tremendously.

I am standing by the beach in Chennai. We are looking east, towards the Andaman Islands, Indonesia and Thailand. The sky is kissed a kind of blue for which purple is an afterthought, a blue that makes me think of the sky at 4 o’clock in New Haven. Women stand in the water wearing white. No one wears a swimsuit, all saris. It is one of my last Sundays here. I have been at the archive today. I have been to the ocean. I have been to my aunt’s university. I have been through great confusion and great sadness. Now, I am thinking of a painting I looked up on my phone on the way here. It is a portrait of Elihu Yale with a few other White men. In the far right corner is a boy, presented as a conceit, I later learn. But in this oil painting he is as plain as day, and he is Black.

Professor Joseph Yannielli — previously a postdoc at the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition — has extensively studied Elihu Yale’s involvement with the Indian Ocean slave trade. I read a lot of his work while I was in India. While some sources seek to portray Yale as an abolitionist, this is counterfactual, Yannielli writes. Yannielli notes that in addition to supporting the Company’s policy of exporting black South Indian slaves to colonies like that on St. Helena, Elihu Yale attended a meeting wherein it was agreed that “a minimum of ten slaves [must be] sent on every outbound European ship … ” At least ten. This is the figure that bothers my father the most. Ten. A number large enough to be a whole family, and small enough to comprehend. Ten. The number of people who left on boats, looking back, looking like him. The number of people who probably never came back.

Yannielli noted that in 1689, Yale sent a ship to the island of Madagascar requesting that slaves be purchased and taken to the colony on Sumatra. While Yale himself didn’t own any slaves, “he profited both directly and indirectly from their sale,” Yannielli said. To me, there isn’t much of a difference. If you traffic in the suffering of others, you are far from exonerated. This wealth is what allowed his money to come to our University, and certainly, Yannielli said, it was what incentivized the University to chase after men like Yale.

I emailed Gitlin on the advice of someone in Yale’s Manuscripts & Archives. I don’t know what I was expecting. Certainly not the response I received. Gitlin believes that “it would also be misleading to characterize [Yale] as a slave trader … Yale’s personal wealth came primarily from a private trade, on the side, in diamonds and other precious gems.” While this may be true, diamonds are far from pure. Diamonds, like the big one on my father’s gold ring. The diamond is from his grandmother’s, my great grandmother’s, nose ring. Even diamonds tell stories. Even diamonds come from somewhere.

“It’s impossible to disentangle the diamond trade from the slave trade,” Yannielli told me over the phone. “The East India Company used the slave trade to consolidate political and economic power, and that power enabled Yale’s mercantile activities.” It is worth recalling that the Company’s initial interest in the subcontinent was to extract natural resources; Yale himself signed “… profitable treaties to the Company’s benefit [that were] … undoubtedly exploitative,” according to an article in the Duke Undergraduate Journal of South Asian Studies by Nikila Sri-Kumar ’11.

The reality is that the slave trade was central to the Yale’s life. Bains notes that “… Yale was part of a broader milieu in both India and England, in which people thought of slave trading and the deployment of slave labor as a political economic strategy …” The Yale Center for British Art possesses a painting in which a black slave can be seen alongside Yale and his compatriots. He is young. He is a child. Defenders of Elihu Yale continually reiterate that Yale himself did not own slaves. Yannielli explained to me that, regardless of whether this is true, Yale is present in two portraits that feature slaves, unusual even for other imperialists.

Yale’s involvement in the slave trade is such a central point in his personal narrative that former Dean of Yale College Jonathan Holloway felt it necessary to preempt a conversation on the issue in his Opening Assembly Address to the class of 2019. “…There’s no doubting the fact that he participated in the slave trade, profiting from the sale of humans just as he profited from the sale of so many actual objects that were part of the East India trade empire,” he said in the speech.

Titus Kaphar ART ’06 had two paintings on display in the Yale University Art Gallery in September of 2016, before I came to Yale. I was drawn to one in particular, titled “Enough About You,” a reconfiguration of the original portrait of Yale and the little boy. The White men in the painting are contorted, their faces and features now missing from the image. All is obscured, save for the boy’s face, framed in gold.

—

This trip to India was my first trip to the subcontinent in a long time. It was my first to Chidambaram, the town south of Chennai where my grandfather is from. The town was built around the temple, which is about 1,100 years old. It is a UNESCO heritage site. Still, people here are casual about the beauty of every archway, the gold statues, the kumkum. I’ve been raised in the United States, where we put things behind glass, explains my father. Here, he says, the history does not get stuck in the past. It’s part of current reality. So they walk casually through temples older than the United States. They inside the memories and outside the reality so that they are intertwined, imbuing one with the other.

When I visit St. Mary’s Church, I see a plaque with Elihu Yale’s name on it. It makes me angry. I want to know why history allowed the name of this man to be immortalized in stone while some, like my great-grandmother’s, go missing. Samuel Delany says that “the language you speak in is the world you see.” I have, as a person of South Asian origin, written this article in English. I attend my classes in English. I live my life in English. I see Elihu Yale’s name carved in that white stone in my first language, in English. Wandering through that church, and here, in these hallways of dark wood and stone in New Haven, I realize: We cannot seek to exist independent of our circumstances. That painting is part of our history at Yale, just like Fort St. George is part of mine. So, too, is whatever was taken out of the ports in my father’s home city and never returned.

The East India Company isn’t here today, but it left a mark on the land. While I am in India, I keep thinking about how lucky I am, finally appreciating everything there. There is so much beauty to be seen, by the beach at sunset and at my grandfather’s temple. The thick smell of honey and sugar, carted in big trucks just in time for Pongal. I have never seen sugar cane stacked so high. There is so much about the universe to love in these small square miles of lush land, especially understanding the violence that was here before, that truthfully, is still here. But sometimes it feels like this gift of sight is coming two generations too late.

In our last visit to the church, I think I understand what my father is saying. In my grandfather’s house, we make sambar with my grandmother Vijaya’s karai. I carry her name in mine. Her stories live with me and color my present. So, too, it is with Elihu Yale. His memory, what he did, who he was, lives in the present for every person in Chennai, but also for us, here, in New Haven.