Cold Cases, Open Wounds

Closure feels out of reach for families of New Haven’s unsolved crimes.

In the break room at work, Sherell Nesmith watched televised news coverage of a mysterious discovery — along the Metro-North Railroad tracks at the State Street train station, someone had scattered dismembered human limbs. On July 15, 2015, the stench of rotting flesh had led a passerby to the location of two severed legs. A bag containing handless human arms was discovered below the Chapel Street bridge.

“I’m watching this and I’m saying — wow, people cutting people up now? Like where do they do that?” Nesmith said. “Not knowing that two weeks later, it was going to end up in my backyard, literally.”

The limbs belonged to her brother, Ray Roberson.

In the intervening three years, his murder has not been solved.

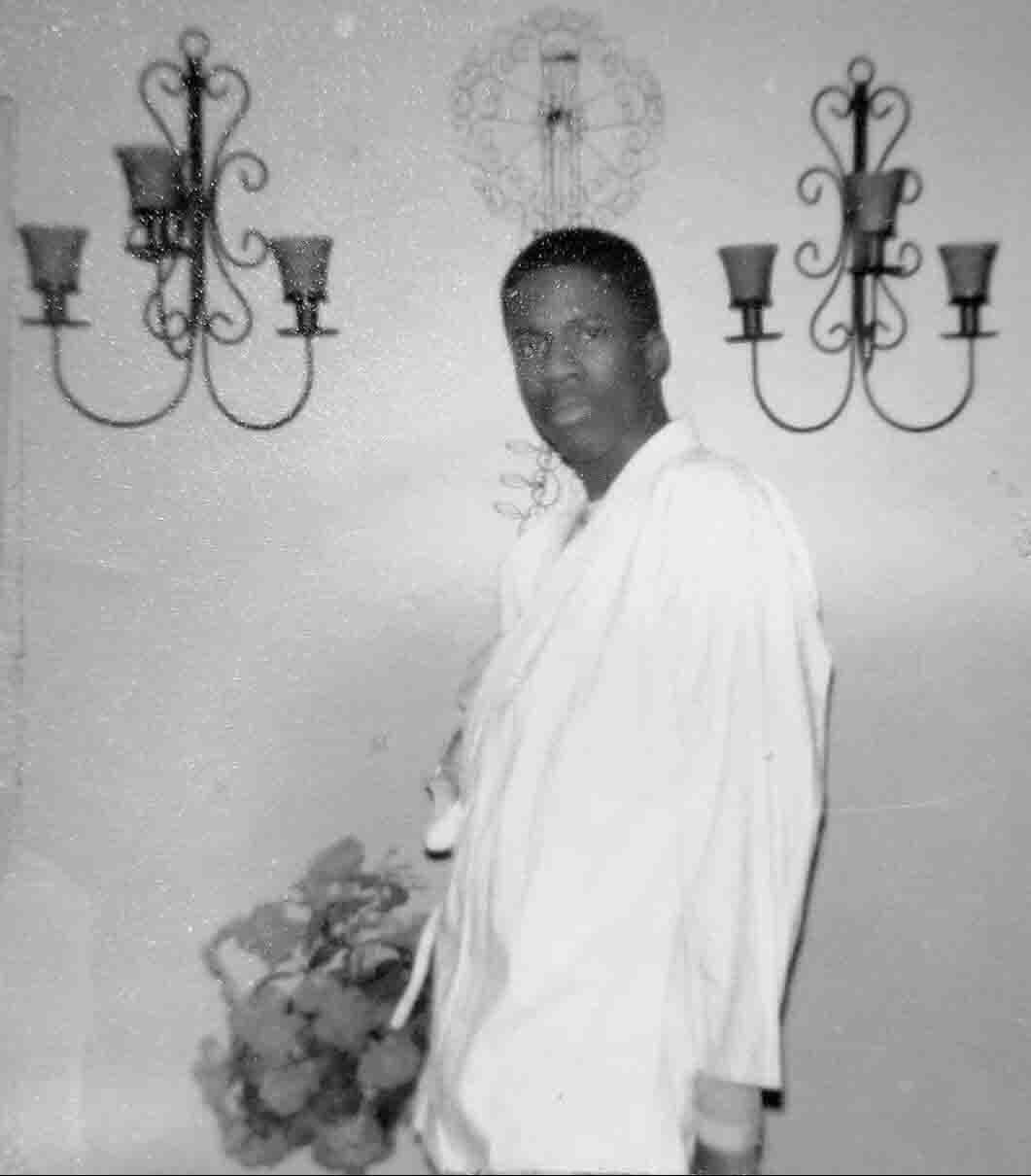

A few weeks after the initial discovery of his legs, police uncovered Roberson’s torso in the abandoned Salvation Army on 274 Crown Street. He was a 54-year-old New Haven resident, a house painter and artist, the eldest of six siblings, affectionately known to family and friends as “Booboo.”

“I think we were all numb,” Nesmith said. “Of course, you cry instantly. But it makes you numb because you’re like, this can’t be. Everybody thinks that these things don’t hit their families.”

Ray Roberson’s murder is an ongoing investigation at the New Haven police. A prevailing sense of anger and mistrust plagues the families of unsolved homicides; grief extends beyond the criminal justice system. Nesmith continues to pray that his case will be solved.

“It’s hard,” she said. “You try to push it back so you don’t think about it, but there are times when you can’t do that. It’s a process where you’re numb. We’re still here. We’ve still got to live. But you don’t ever forget about it.”

Some families seek closure through arrests and convictions, a difficult process in open cases. Ongoing investigations serve as daily reminders of painful events they wish to leave behind.

“Some people are fortunate in the atrocity that they may know who [the killer] is,” she said. “But there are some of us whose crimes may be elongated.”

—

In 1998, Yale senior Suzanne Jovin was found fatally stabbed in the back near the corner of Edgehill and East Rock roads. Dec. 4, 2018 marks the 20th anniversary of her murder.

“From our perspective, this year is no different than any before,” the victim’s parents, Donna Arndt-Jovin GRD ’68 and Thomas Jovin, shared in an email with the News. “Suzanne was a good citizen (and a good student) of Yale, was happy there and derived great benefits from an outstanding institution of higher learning.”

On the night of her murder, she was walking back to campus from a pizza party for the New Haven chapter of Best Buddies, an international organization dedicated to serving people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. A celebrated member of the Yale community, she posthumously received the Special Elm and Ivy Award from The Community Foundation for Greater New Haven in 1999. There are numerous dedications honoring her contributions to the Yale community, including a memorial plaque in the Davenport College courtyard. The Suzanne N. Jovin Memorial Fund continues to support promising undergraduate students who “reflect Suzanne’s aspirations and commitments.”

Over the intervening 20 years, the Jovins have maintained close contact with public investigators in New Haven. They are still searching for conclusions to be made about the circumstances of her death. In an email to the News, her parents credited the University as an “outstanding institution of higher learning.” But they urged the University to finally share the information gained by its private investigators with the New Haven and Connecticut authorities.

“For whatever reason, the University has opted, at least up to now, not to release the material,” the Jovins wrote. “We by no means condemn the University, merely urge it to join us in facing the challenges generated by the violence that is so prevalent in our society.”

University spokesperson Karen Peart stated that Yale “has cooperated fully with the investigation and has provided all available information that the law enforcement authorities have requested.”

—

According to the Division of Criminal Justice, Jovin’s case is one of 38 open cold cases in the state of Connecticut. Many are serious crimes or homicides of decades past, ranging from the 1968 abduction of 13-year-old Debra Spickler to the 2012 Waterford shooting of Kyle Seidel.

In an effort to dedicate special resources to the investigation of unsolved crimes, the Connecticut Office of the Chief State’s Attorney established its Cold Case Unit in 1998. Central to the core of its mission is the idea that every case, no matter how old, deserves to be solved. As the Senior Assistant State’s Attorney for the New Haven Judicial District, Seth Garbarsky works with a team of 25 law enforcement individuals to prosecute felonies for the state of Connecticut. Although a majority of homicides in the New Haven County occur in the City of New Haven, his role extends to cover any and all cases in the County’s jurisdiction, including the murders of Ray Roberson and Suzanne Jovin.

“The primary function of a cold case unit is to look into cases that for whatever reason have (been) deemed to have gone unsolved. It’s just to put a new, fresh pair of eyes,” Garbarsky said. “It could be a case that’s two weeks old; it could be a case that’s 20 years old. … It’s not a very exact science.”

The Governor’s Office authorizes thousands of dollars for information leading to arrests and convictions in open cold cases. Sizes of rewards vary by case; the maximum state commitment is $50,000. Additional funds come from the families and communities of murder victims. In the case of Suzanne Jovin, Yale University has offered $100,000 in addition to the state’s $50,000, making the total cash reward the largest in Connecticut.

Authorities work with a wide range of sources for potential leads. “That could be family members; it could be eyewitnesses; it could be witnesses that are cooperating from prison — jailhouse informants,” Garbarsky said. Fluctuating budget cuts and limited access to resources requires creative methods to find tips on unsolved crimes.

In 2010, the Cold Case Unit released the first edition of cold case playing cards, each card featuring a picture and brief details about an unsolved case. Since then, the unit has received 675 tips on open cases, leading to 20 arrests and convictions. A total of four editions have been distributed through the Connecticut correctional system. The fourth and current edition was released just last month.

Rapid advancements in forensic science also help to uncover previously unknown details, allowing new methods of application towards criminal investigation. It was postmortem DNA testing that led to the identification of Roberson’s dismembered body. DNA identification allows authorities to gather DNA from articles of clothing, surfaces and other pieces of evidence.

“Every day, there is constant advancement in this field, which obviously goes to help us, Garbarsky said. “It also goes to exonerate individuals who were found not to have committed a crime.”

Garbarsky’s work is inextricably linked to legitimizing the grief of the living.

“I don’t even think it has anything to do with a punishment or jail or incarceration,” he said. “I think [families] just want to know who did this horrific thing and why they did this horrific thing. I think that’s why we continue to investigate — to give the families some sense of justice and closure.”

—

Life goes on despite the tragedies of injustice. For Winter Alston, the news of her brother Iroquois Alston’s death coincided with her son’s first birthday on Aug. 6, 2011. She was shopping for the birthday party with her mother when she received the call. They rushed to the scene of the shooting only to be stopped by police — “I told them I was his mother,” April Barron said. He had been shot in the back of a Honda sedan, along with his friend Rickita Smalls. That night, Alston identified her brother’s belongings in an evidence bag at the Norwalk police station.

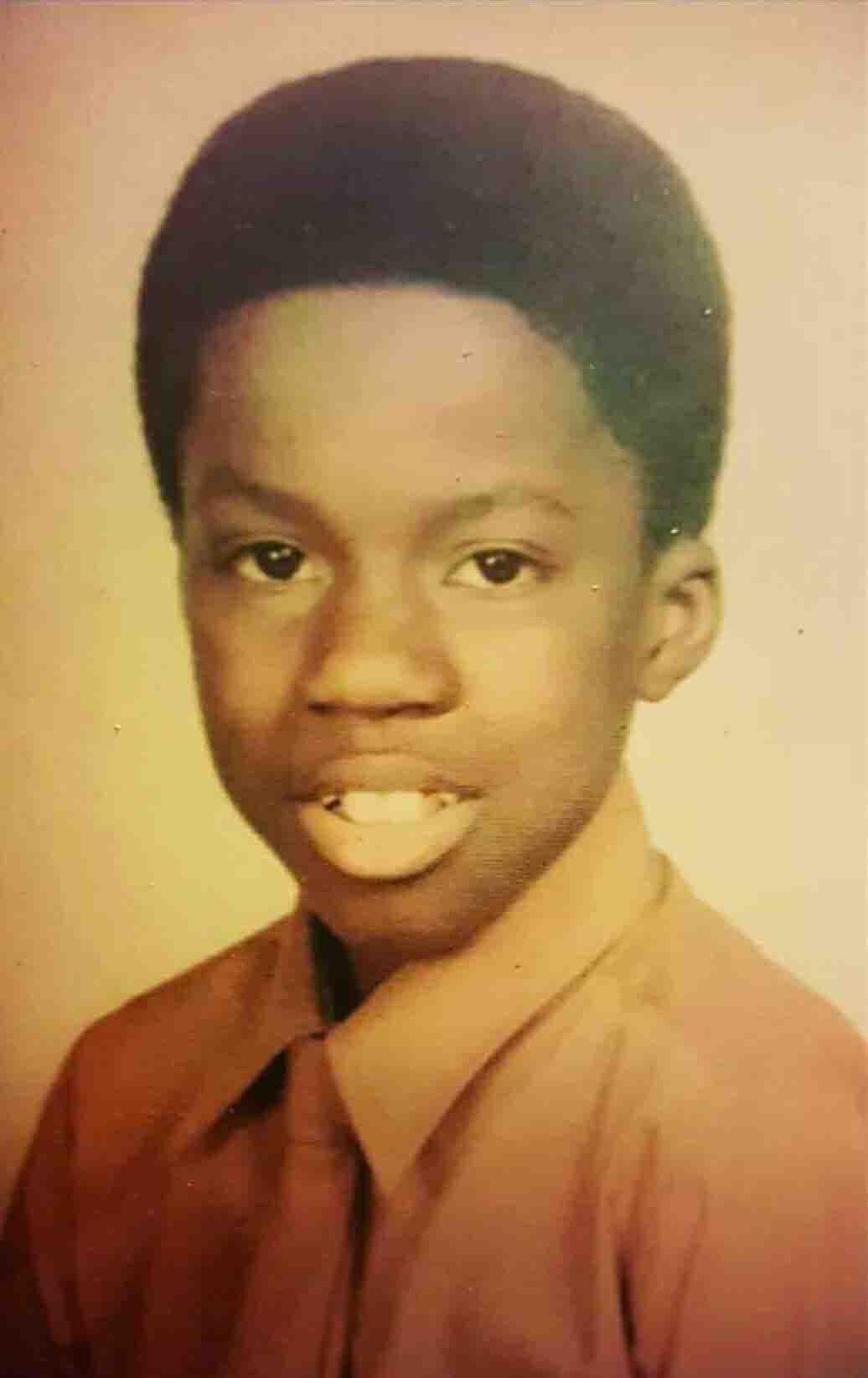

Alston, 27 at the time of his murder, was a loving father and dedicated son.

“He was always smiling. There was never a dull moment around him,” his daughter Dynasty Alston said.

A family member’s passing is a difficult process to endure, his murder an unexplainable reality to communicate to his child. She remembers being pulled from dance practice and rushed to her grandmother’s house.

“Nobody wanted to tell me what was going on. I had to beg to find out,” she said. “I think about it a lot. I’m more angry if anything. … It’s hard. It’s a lot to take on.”

Seven years after Iroquois Alston’s death, his family has cycled through four police detectives, made countless weekly calls and prayed daily. Barron, Alston’s mother, calls the Norwalk police “three to four times a week” to inquire about new progress. It is a tireless task of never-ending grief, the presence of unceasing sorrow in the absence of her son.

“May 26, 1984 was the best day of my life, and Aug. 6, 2011 was the worst,” she said.

The Alstons have remained in contact with the family of Smalls, the woman also found dead in the sedan. Since the murder, they have relied on each other in times of need.

“We just need justice,” Alston’s daughter said. “It’s been going on too long now. Seven years and nothing. He’s still not here. They still took a life. Whoever did this is still somewhere walking around.”

—

Sherell Nesmith frequently communicates with the New Haven police, serving as the point person to represent her family in the case. Overcoming her grief to maintain an active role is an essential part of honoring her brother’s passing.

“In the beginning, [the detective] was present quite often. As time goes on, you hear from them a little less. If they get something, they’ll reach out to you. But he’s always made it very clear, ‘If you have any questions, I’m a phone call away. You call me. You text me. We can get together.’”

Over time, it is perhaps inevitable that cold case investigators become an important part of grieving families’ lives, acknowledging that victims of unsolved homicides include the living.

“When I’m walking around throughout the city, I’m looking like — could it be that person? — your mind is all over the place,” said Nesmith. “It’s just a matter of trying to stay sane because it never goes away.”

An arrest or conviction comes at the cost of personal hardship; families of the deceased endure years of grief in search of closure.

“My response then and my response now is: There’s a special place in hell with [the killer’s] name on it,” she said, echoing a sentiment repeated by the Alstons. “One day [they] are going to meet those fiery pits of hell.”

They share their stories in honor of their loved ones, as Nesmith said, to “keep his name out there until justice has come.”