Our HIV crisis:

Reclaim the spotlight

T

wo weeks ago, I was talking to history professor George Chauncey ’77 GRD ’89 when he reached back into his memory to describe the late professor John Boswell. He couldn’t find words of his own, so he relied on a story. One day while walking out of Boswell’s undergraduate lecture, he overheard a student talking to a friend. The student excitedly proclaimed, “You see what I said about how amazing his lectures are. It’s like he’s in an opera!”

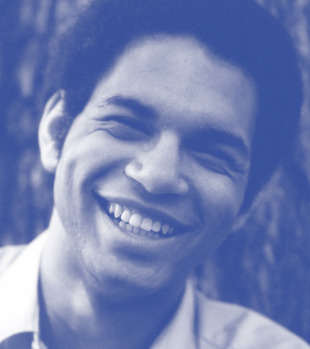

John Boswell

(The Yale AIDS Memorial Project)

Chauncey paused, as I am sure he did when he told the same story at Boswell’s memorial service 20 years ago, and said, “He was right. And Jeb was our diva.”

I suppose when someone commands a place in the spotlight, it brings both the adoration of an attentive audience as well as their sorrow during the ensuing tragedy of his death. By this standard, Boswell was indeed a diva.

Boswell joined the Yale faculty at age 28, won the National Book Award at age 33, taught a famous Yale lecture and fathered the concept of lesbian and gay studies here at Yale. In late 1994, at age 47, Boswell also joined the scores of Yale community members who lost their battle to HIV/AIDS.

The Yale AIDS Memorial Project’s website catalogs memories of some of these men:

David W. Dunlap ’74 still remembers a night with Warren Smith ’74, who died of AIDS-related complications: “We got into bed and looked at one another across the space of the pillow. And it was, ‘Are you thinking what I’m thinking?’ And, ‘I think I am.’”

Bill Rubenstein ’82 still remembers John Wallace ’82: “Our senior year at Yale, John and I had been in an American Studies reading group together, and I sat across the seminar table mesmerized by his beauty while everyone chattered on about the social significance of Barbie dolls and ‘Graceland’ and ‘My Mother the Car.’”

John Wallace ’82

(The Yale AIDS Memorial Project)

Reading over the transcript of Chauncey’s remarks at Boswell’s memorial service, I couldn’t help but notice something: Chauncey lauded John Boswell’s extraordinary gifts and his efforts that helped make Yale the “gay Ivy.” He spoke of members of the University who would yearn for his presence. But he didn’t say that the University would miss him. The implication was that Yale would move on. At first I thought this was an unintentional omission, but then I realized it wasn’t.

Even the most profound experiences and people will fade from campus memory as, year by year, the composition of the student body and the faculty changes. The unyielding churn of the University all but ensures that one’s Yale experience remains personal and not institutional. This produces an unfortunate result: Because the student body evolves, the concerns of a class year or a series of class years, left unruffled on the shelves, fade from memory. Individuals might remember John Boswell, John Wallace and Warren Smith. But Yale University as a body does not; it has moved on from its struggle with HIV.

Yale sacrificed many of its sons to the epidemic, but their identities seem lost in the past.

The University has failed because, like everyone else, it let a welcome shift in the meaning of a positive HIV diagnosis — from acute infection and certain death to chronic illness — absolve it of its responsibility to act. People stopped dying around us, so we have stopped caring, stopped remembering and haven’t taken the active steps necessary to secure an HIV- and AIDS-free generation. It is no longer a priority.

Warren Smith ’74

(The Yale AIDS Memorial Project)

Next month, many young gay men, myself included, will leave this campus and flock to metropolitan areas. Some will move to cities like Atlanta, where nearly half of newly diagnosed HIV cases at Grady Hospital have already progressed to AIDS. Others will take up residence in New York, where a large white and upper-class gay population acts as a buffer to transmission. Some will avoid HIV. Others will help fulfill the prediction that 50 percent of young gay men will contract this race- and class-segmented virus in the next 30 years, likely suffering unwarranted shame and isolation in their post-college years.

But for some reason, on this campus, we relegate the issue of gay men’s health to a tiny office in Swing Space and the generic advice, “Use a condom.”

Yale needs to step up its game. But until then, we, the students, gay and straight, must take up the charge, both here on campus and when we leave. Let’s reclaim the spotlight Boswell left behind. We can be divas too. We can refuse to exit the stage.